Transactions as Transformers

Database transactions are traditionally modeled as a sequence of read/write operations on a set of keys, where each read operation returns some value and each write sets a key to some value. This is reflected in most of the formalisms that define various transactional isolation semantics (Adya, Crooks, etc.).

For many isolation levels used in practice in modern database systems, (e.g. snapshot isolation or above), we can alternatively consider viewing transactions as state transformers. That is, instead of a lower-level sequence of read/write operations, a transaction can be viewed as a function that takes in a current state, and returns a set of modifications to a subset of database keys, based on values in the current state that it read. This view is not fully general in its applicability to all isolation levels (e.g. read committed), but we can explore this perspective and how it simplifies various aspects of reasoning about existing isolation levels and their anomalies.

State Transformer Model

Most standard formalisms represent a transaction as a sequence of read/write operations over a subset of some fixed set of database keys and values e.g

\[T: \begin{cases} &r(x,v_0) \\ &r(y, v_1) \\ &w(x, v_2) \\ &r(z, v_0) \end{cases}\]For transactions operating at isolation levels that read from a consistent database snapshot, though (e.g. Read Atomic and stronger), we can think about transactions as more cleanly partitioned between a “read phase” and “update phase”. That is, we can consider the “input” of a transaction as the subset of keys it reads from its snapshot, and its “output” as writes to some subset of keys, each of which, at most, can depend on some subset of keys that were read from that transaction’s snapshot. In other words, at levels like snapshot isolation, although a transaction seems to pass through many stages, doing reads and writes internally, we can compact these stages down into a single read and update phase.

We can formalize this idea into the view of transactions as state transformers. For example, for a database with a key set \(\mathcal{K}=\{x,y,z\}\), we can consider an example of a transaction modeled in this way:

\[T: \begin{cases} &\mathcal{R}=\{x,y\} \\ &x' = f_x(y,z) \\ &y' = f_y() \end{cases}\]In this representation, \(\mathcal{R}=\{x,y\}\) is the set of keys read by the transaction upfront, and each \(f_k\) is a key transformer function i.e. a pure function describing the updates that get applied to each key \(k\) that is being updated by that transaction. Each such function can optionally depend on the values read from the current snapshot state for that transaction. We can refer to the set of keys passed as arguments to a key transformer as the update dependencies of a key.

Note that we separate transactions into “read” and “update” portions, where the read-only phase is considered to happen upfront and may or may not be over a different subset of keys than exist in the update dependencies of the key transformers. We might choose a different model where transactions only consist of the key transformer functions, but the above allows us to also include read-only transactions in our model.

Isolation Anomalies and Lost Update

Viewing transaction operations as being composed of these key transformer functions i.e. functions that read some values and produce some writes, helps clarify some awkward aspects of existing transaction isolation models and their treatment of anomalies. Particularly due to the fact that most traditional transaction formalisms don’t make these kind of update/transformer operations an explicit first-class member of their formal model.

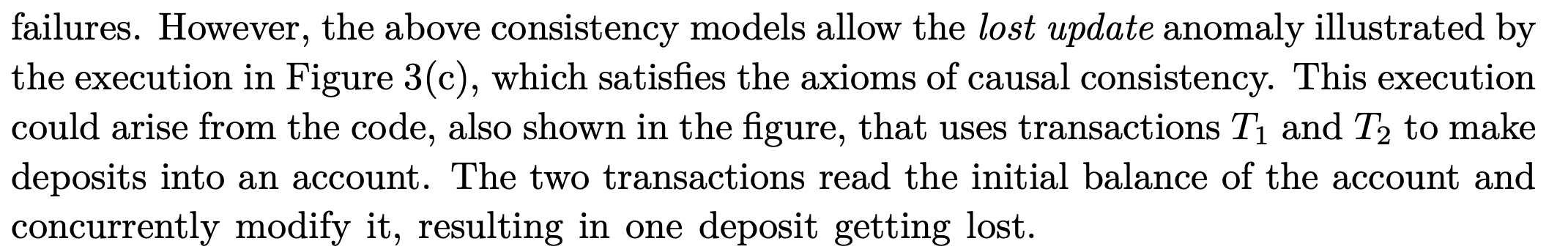

For example, we can consider some standard treatments of the lost update anomaly. In the Cerone 2015 framework, they represent transactions as sequences of read/write operations over a set of keys.

When they define the lost update anomaly in their model, though, it sort of requires skirting the issue a bit by resorting to a notion of “application code” that could have produced this sequence of writes:

This is common across many other descriptions of the lost update anomaly. One unsatisfying aspect of these descriptions of lost update is that the underlying formalism doesn’t seem to do an accurate job at capturing the underlying reason for the anomaly occurring. In addition, lost update is presented often as the canonical anomaly that “write-write” conflicts in snapshot isolation (SI) exist to prevent. But, if we removed the reads from the \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) in the above example, this SI approach to preventing lost updates would need to still abort one of the transactions, but it’s not really clear why that is necessary, since the notion of “lost update” goes away when both transactions are doing only writes, albeit to the same key.

One view is that anomalies like lost update (which are the specific anomaly which write-write conflicts in snapshot isolation are supposed to prevent), are fundamentally unnatural to express without resorting to some model that can take into account the true “update” semantics (e.g. read-write dependencies) between transactions. In other words, the underlying problem of “lost update” arises due specifically to a case where a write is done that is dependent on a value that was read in that transaction. Most formalisms don’t make this “write that depends on a read” semantics explicit, though, and so resort to a kind of vague notion of “application code” that might have done such updates.

In the state transformer model, we might say that a more precise definition of lost update is the case where two transactions \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) update the same key \(k\) via key transformers \(f^{T_1}_x\) and \(f^{T_2}_x\) and \(k\) is a dependency of one of these transformer functions e.g.

\[\begin{aligned} f^{T_1}_x(x) = x + 1 \\ f^{T_2}_x(x) = x + 3 \end{aligned}\]That is, a lost update is a problem specifically due to the read-write dependency that exists between the two transactions. This creates a potential serializability anomaly since, if you execute two transactions with transformers as in the above example, the order of these transactions matters for the final outcome, since they incur a semantic (read-write) dependency on each other. That is, if they both execute on the same data snapshot and are allowed to commit, the result will be semantically incorrect i.e. you really have “lost” one of the updates, since the outcome will be either \(x=1\) or \(x=3\), but not \(x=4\) as it should be (assuming \(x=0\) in the shared snapshot).

Similarly, such an anomaly can also arise with a different dependency structure e.g.

\[\begin{aligned} f^{T_1}_x&() = 6 \\ f^{T_2}_x&(x) = x + 3 \end{aligned}\]In this case, the order of execution can matter, but if these transactions are concurrent and \(T_1\)’s write were allowed to “win”, then we end up in the state \(x=6\), which is equivalent to a scenario where the transactions executed serially with \(T_2\) going first. If \(T_2\)’s write “wins”, though, then we end up in a state where \(x=3\) which is not equivalent to either serial execution of these transactions, which produces either \(x=9\) or \(x=6\).

Finally, we can also have a case where both transactions perform “blind” writes to the same key, incurring no dependency on each other, e.g.

\[\begin{aligned} f^{T_1}_x() &= 6 \\ f^{T_2}_x() &= 3 \end{aligned}\]In this case, no true lost update anomaly can manifest, since the resulting state after commit of both transactions will always be equivalent to their execution in some sequential order. Essentially, existing transaction formalisms can be seen as behaving as this case i.e. where all key transformers have no key dependencies. That is, they always write “constant” values i.e. those that are not dependent on any values read by the transaction.

Write Skew and a Generalized View of Anomalies

This transformer model also gives us a way to see that lost update can really be seen as a special case of a more general class of anomalies. In particular, two transactions writing to the same key is not a fundamental condition for this class of anomalies, it just occurs in the lost update special case.

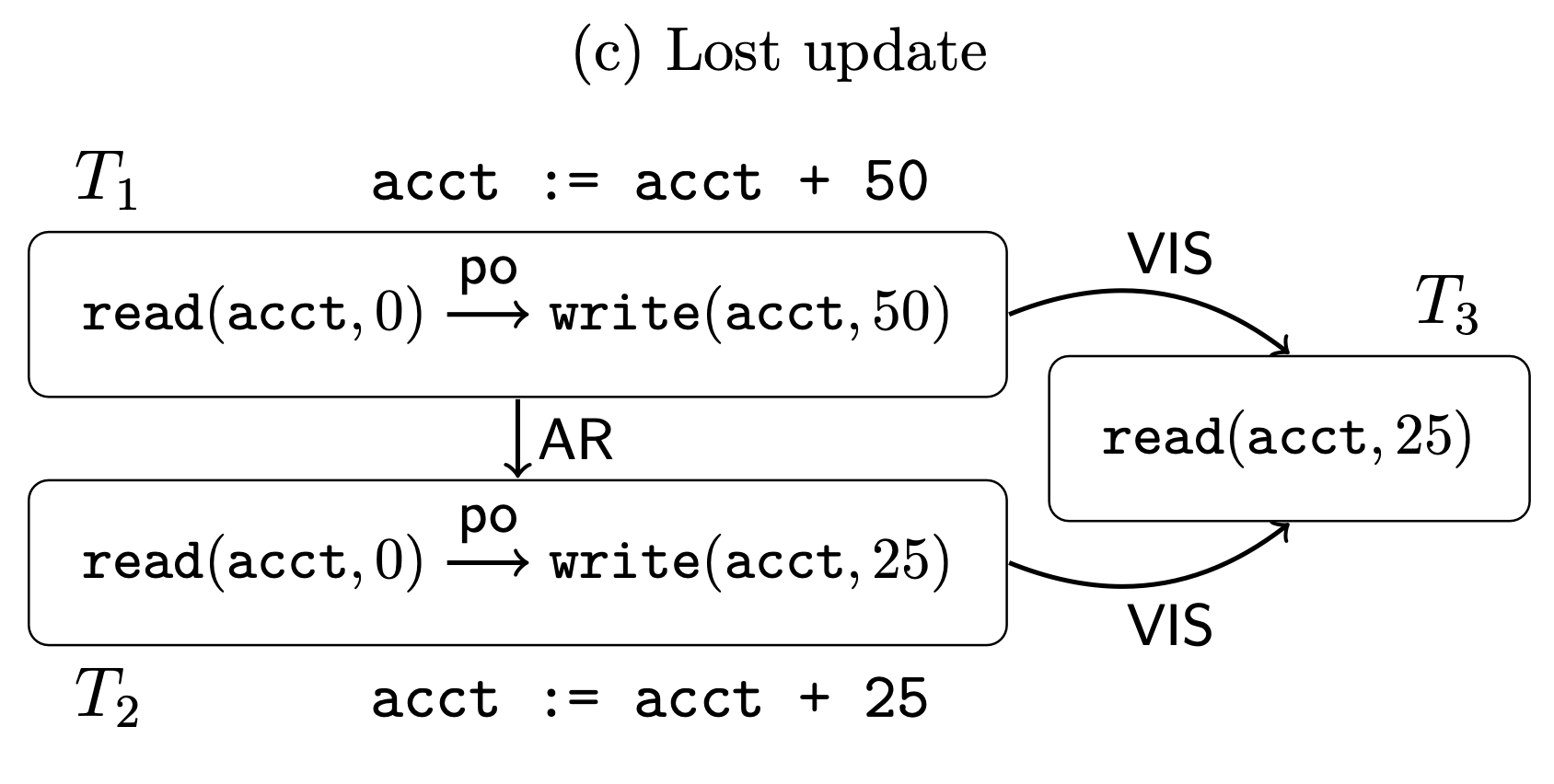

For example, we can also consider write skew within this framework, the canonical anomaly permitted under snapshot isolation. The classic write skew example manifests when two transactions don’t write to intersecting key sets, but they both update keys in a way that may break some external “semantic” constraint. As illustrated again in Cerone by example:

We can represent this example in the state transformer model as something like:

\[T_1: \quad \begin{aligned} f_x(x,y) &= \text{if } (x + y) > 100 \text{ then } (x - 100) \text{ else } x \\ \end{aligned}\] \[T_2: \quad \begin{aligned} f_y(x,y) &= \text{if } (x + y) > 100 \text{ then } (y - 100) \text{ else } y \end{aligned}\]In this case, even though transactions \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) write to disjoint keys, the key transformers in each transaction depend on both keys, \(x\) and \(y\), based on their conditional update logic. Again, the core problem here arises due to the read-write dependencies between these transactions i.e. the writes of one transaction affect the update dependency key set of the writes (i.e. key transformers) of the other. Thus, their order of execution matters, and so the resulting state will not be equivalent to some serial execution.

When viewed in this perspective, it is clearer to understand lost update and write skew as special cases of a more general class of anomalies that can arise when there are data dependencies between the write set of a transaction and the update dependency set of another transaction. This provides a more general view of this type of anomaly e.g. these arise when there exists some read-write dependencies between a set of transactions.

For example, we can also consider subtle variations on the standard write-skew example:

\[\begin{aligned} T_1: \quad &f_x(y) = y - 50 \\ \\ T_2: \quad &f_y(x,y) = y + x \end{aligned}\]This isn’t quite the same as the classical write skew constraint violation example, but it can still cause a serialization anomaly. For example, from a starting state where \((x=100, y=200)\), executing both transactions concurrently (i.e. against the same snapshot) ends us in a state where

\[(x=150, y=300)\]whereas serial execution gives us either

\[(x=150, y=350)_{T_1 \rightarrow T_2}\] \[(x=250, y=300)_{T_2 \rightarrow T_1}\]The state transformer model also sheds light on various quirks of default transaction isolation definitions and implementations that appear somewhat confusing or ad hoc when you examine them in more detail. For example, in classic snapshot isolation, write-conflicts force two transactions to conflict and one to abort if they both write to the same key. In theory, this behavior exists to prevent lost update anomalies, as mentioned above. In reality, though, this is a very coarse-grained and conservative way of trying to prevent these anomalies. Really, what we care about is aborting a write that depended on a value read that was written by another transaction. Aborting write conflicts is just one way to prevent the particular “lost update” special case (i.e. when two transactions directly write to the same key), doing nothing to handle write skew and the more general class of update-based anomalies. Moreover, it is done in an overly conservative way e.g. if two transactions do no reads but write to the same key, there is no strict need to abort either of them, though one of them must be aborted under most snapshot isolation implementations.

Similarly, there are related workarounds in other models where a basic notion of “read set”/”write set” conflicts is not precise enough. For example, in A Critique of Snapshot Isolation, they make the simple but clever observation that detecting read-write conflicts (rather than write-write) is sufficient to make snapshot isolation serializable. But, even here, they have to add a particular special case for read-only transactions e.g.

Plainly, since a read-only transaction does not perform any writes, it does not affect the values read by other transactions, and therefore does not affect the concurrent transactions as well. Because the reads in both snapshot isolation and write-snapshot isolation are performed on a fixed snapshot of the database that is determined by the transaction start timestamp, the return value of a read operation is always the same, independent of the real time that the read is executed. Hence, a read-only transaction is not affected by concurrent transactions and intuitively does not have to be aborted….In other words, the read-only transactions are not checked for conflicts and hence never abort.

When viewed in the state transformer model, we can see why read-only transactions are not needed to be checked for conflicts, since none of these reads are used in an update dependency key set. Anomalies of this class only arise when you take into account reads that are used as a part of a true “update”, which most models just don’t explicitly represent.

Another related aspect is that the transformer based view can theoretically assist in finer-grained conflict analysis between transactions. For example, in the write-snapshot isolation approach, any transactions that do writes may be prone to abort due to a read-write conflict (i.e. they read a key that was written by a concurrent transaction). But, if transactions have very large read sets, this can make them very prone to aborts, since their read conflict surface area is large. But, we should really only need to be concerned with those keys that are read and used in some update dependency set in a key transformer of that transaction e.g. it is possible we may read 1000s of keys in a transaction, but only a small number of these keys are used in an update dependency.

The state transformer model helps to see many of these special anomaly cases in a unified way e.g. two write-only transactions that conflict in the transformer model can be understood as both having transformer functions with empty key dependency sets, so no conflict manifests by the conflict rules of this model. Similarly, for read-only transactions i.e. if you do reads but none of these reads are actually used as dependencies of a key transformer function, no conflict needs to be manifested.

Overall, given a set of transactions that may be executing concurrently, we can say that, in our state transformer model, some serialization anomalies (and therefore conflicts) may arise if there exists dependencies between the write set of a transaction and the key transformer dependency set of another transaction. This serves as a way to generalize both lost update and write skew anomalies into a broader, unified class of anomalies. Furthermore, it becomes clear that special cases like “write conflicts” or “lost updates” are not fundamentally related in any way to “transactions writing to the same key”, but rather a case of the general problem of these update dependency relationships.

Merging and Deterministic Scheduling

This state transformer view of transactions also opens up a few interesting questions about whether we can be smarter when thinking about conflicts. That is, if transactions are formally expressed in this state transformer structure, we could consider cases where, instead of aborting transactions that encounter certain type of conflicts (write-write), we may consider semantically merging the effects of their key transformers into a unified operation that reflects the correct, sequential execution of both transformers. This is in essence similar to CRDT-based ideas, but applied in the context of a more classic transaction processing paradigm. Similarly, we might consider related ideas on “re-execution” e.g. we could imagine that, if a conflict is detected from a concurrent transaction writing into your update dependency key set, it may be fine to simply re-compute the result of your update based on the written value, dynamically “correcting” the serialization anomaly.

Similarly, if transactions can be represented in this fashion for most practical systems/isolation levels, this also seems to raise the question of whether we can also apply ideas from deterministic transaction scheduling (i.e. Calvin style), since in theory the read/write sets of a transaction are known upfront. In practice, many transactions may still determine their full read/write sets dynamically (or via predicates), as they execute, but it may still be useful to model transactions within this formalism, even if it doesn’t fully align with the execution model in practice.

Note that the existing world of stored procedure transactions, and one-shot transaction models like those described in Spanner, share similarities with this state transformer view of transactions. It is also similar to some formal reasoning arguments that talk about moving all reads to the beginning of a transaction, and all writes to the commit point, to simplify reasoning. It may be helpful, though, to consider this type of model a more fundamental part of the isolation formalism itself.