Logless Raft

The standard use of Raft is for implementing a fault tolerant, replicated state machine by means of a replicated log, maintained at each server within a replication group. Depending on the nature of the state we want to replicate, we can employ a simpler variant of Raft that achieves the same essential correctness properties. We can call this logless Raft and it can be useful when we are only replicating a single, small piece of state (e.g. configuration, metadata, etc.) between servers.

Simplifying Log Management

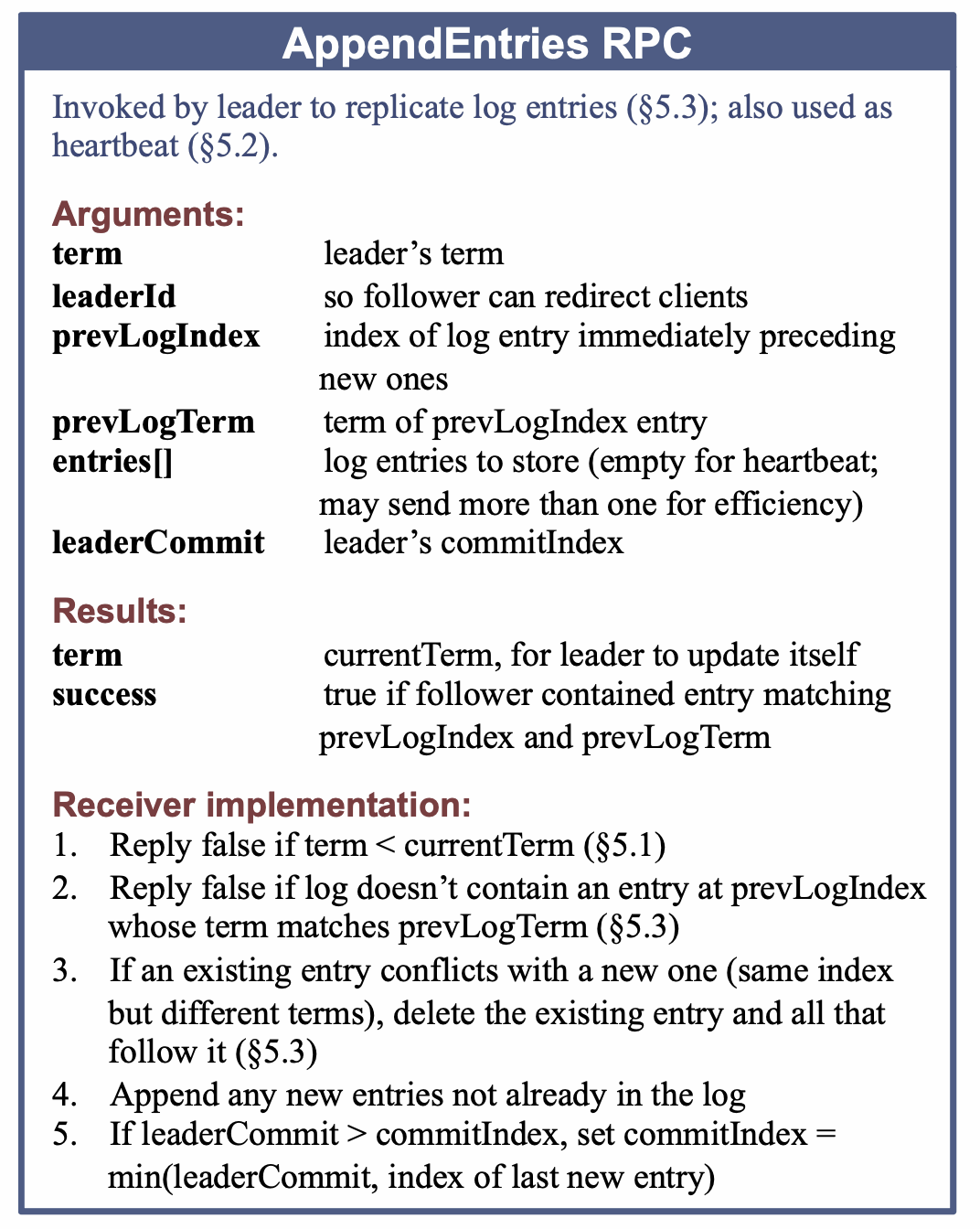

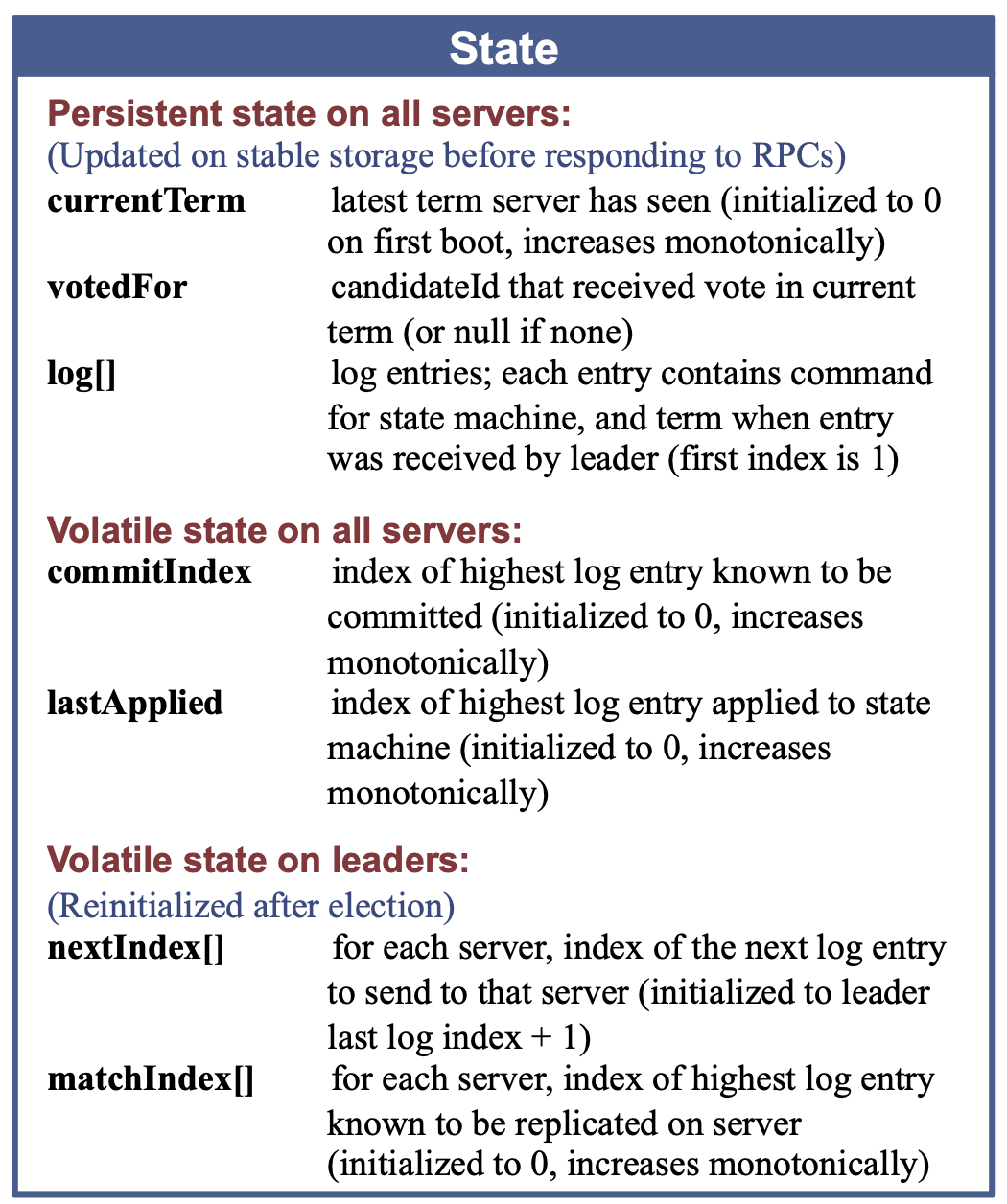

There is a lot of machinery included in the standard descriptions of Raft related to the intricacies of replicating log entries between servers, recording the applied indices of the log on each server, etc. (e.g. matchIndex,nextIndex,commitIndex). There are also strategies for specifically dealing with clean up and garbage collection of stale, divergent logs, handled as part of the AppendEntries request/response flow.

Most of this log and index management machinery is bookkeeping around what log entries a node (e.g. a leader) should send to other nodes (nextIndex), what entries other nodes have received so far (matchIndex), and which entries have been marked as committed (commitIndex). These details may be required from an implementation perspective, but from a protocol correctness perspective they are somewhat extraneous.

We can reduce this complexity with a variant of Raft that gets rid of the lower level implementation details around log index management and propagation of this information. Instead, Raft servers can send their entire logs to each other in each message. Receiving nodes can, based on their local log state and the log they received, determine which entries (if any) they can go ahead and append to their own log. Individual nodes no longer track any of the nextIndex/matchIndex bookkeeping variables, and the information flow between leaders/followers can also become more symmetric e.g. both can propagate their entire logs to each other as a way of communicating new updates or feedback about which log entries have been appended.

Log Merging vs. Log Replication

In this model, both log append and log truncation operations, normally incremental processes that may occur via repeated rounds of AppendEntries messages from a leader, are subsumed into a single log merge operation. That is, when a node \(i\) receives a log from node \(j\), it determines whether it can install this incoming log based on certain conditions.

At a high level, these conditions can be expressed as a check whether a node \(i\)’s own log, \(log[i]\) is a prefix of \(log[j]\). If so, it is safe for the node to extend its log to the received log, by updating \(log[i]\) to the value of \(log[j]\). If \(log[i]\) is not a prefix of \(log[j]\), then it must check for a “staleness” or “divergence” condition, by comparing the last term of both logs. If \(i\)’s log has an older last term than \(log[j]\), then it is safe to replace \(log[i]\) with \(log[j]\). Otherwise, it is not safe to modify its own log.

In both cases, this “prefix” check can be implemented in Raft by simply comparing the last term of each log, similar to how logs are compared in standard vote requests in Raft. That is, if the terms of the last entry in each logs are the same, then the prefix check can be done by comparing log lengths, and otherwise, the check is done by comparing the terms of the last entry in each log, with newer terms taking precedence.

A simplified version of this Raft variant is defined in this TLA+ specification (along with an explorable version). In that specification the MergeEntries action represents the key “log merge” operation, and encodes the log prefix checking rules for both append and/or garbage collection.

A Closer Look at Raft Log Structure

We can gain some additional intuition on the above merging view with another, closer look at the way that logs are structured across nodes in classic Raft. Specifically, we can view the set of all node logs as forming a global log tree structure, where each node’s local log is a “view” on this global tree e.g. a local log can be seen as a path in this tree. Over time, new branches may be created or pruned from this tree (e.g. via log truncation), and nodes may sync their local logs to move back in sync with (newer) branches.

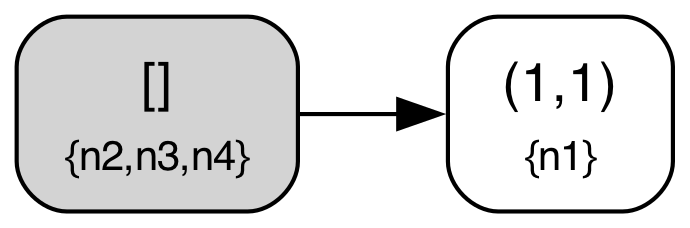

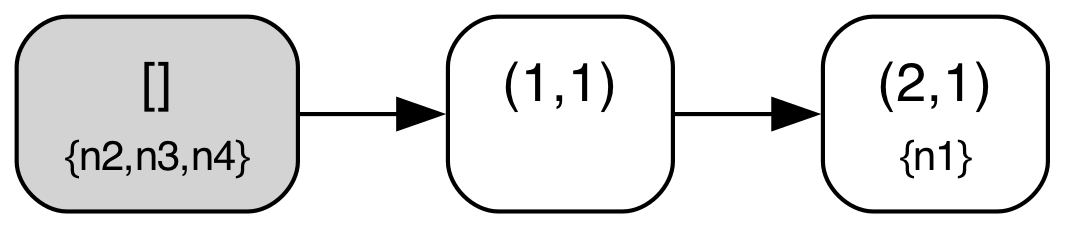

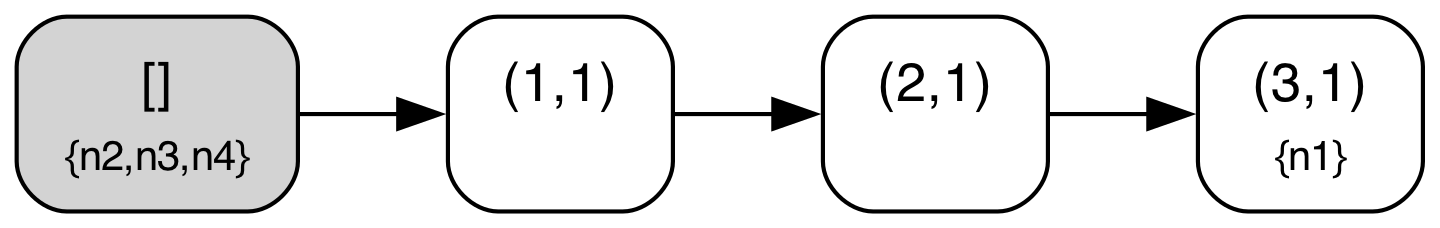

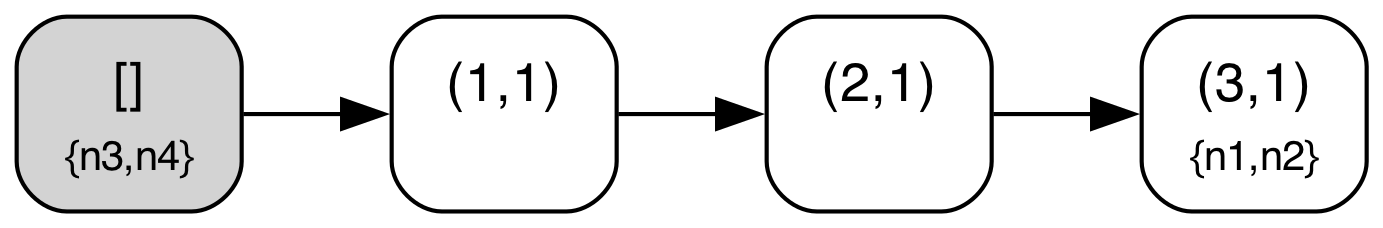

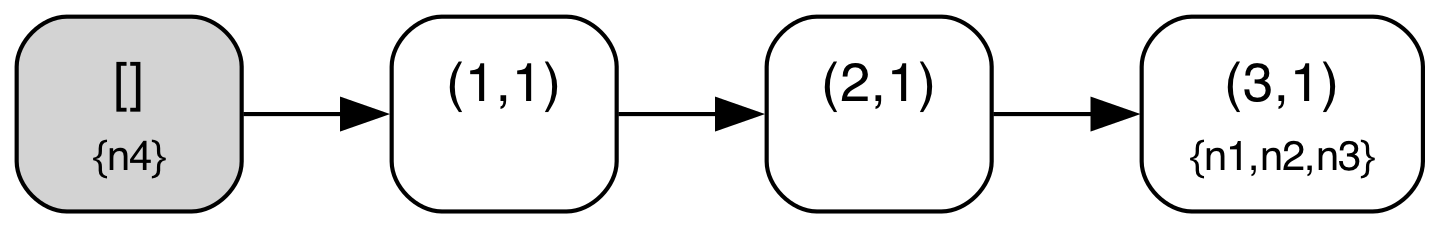

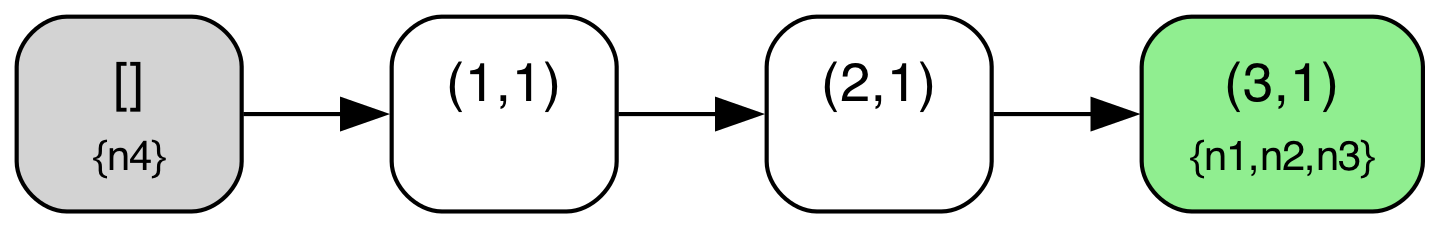

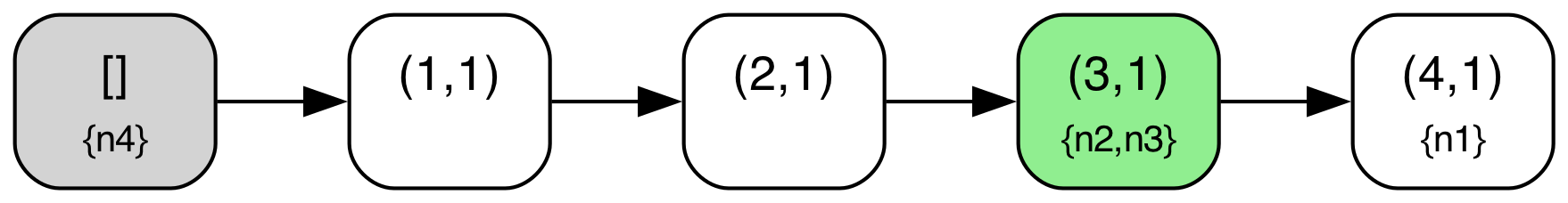

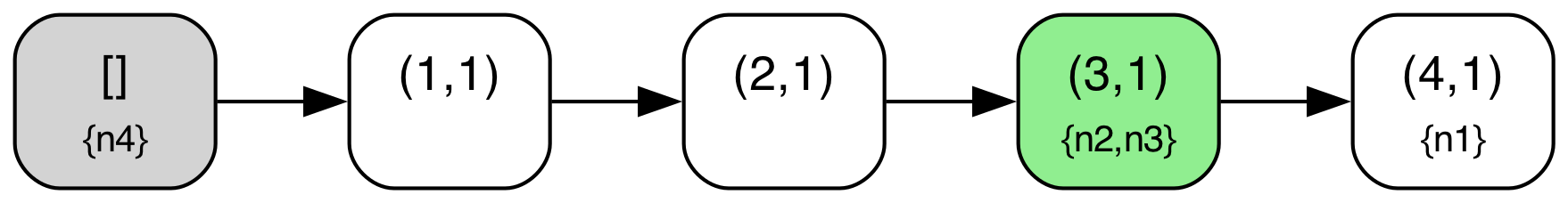

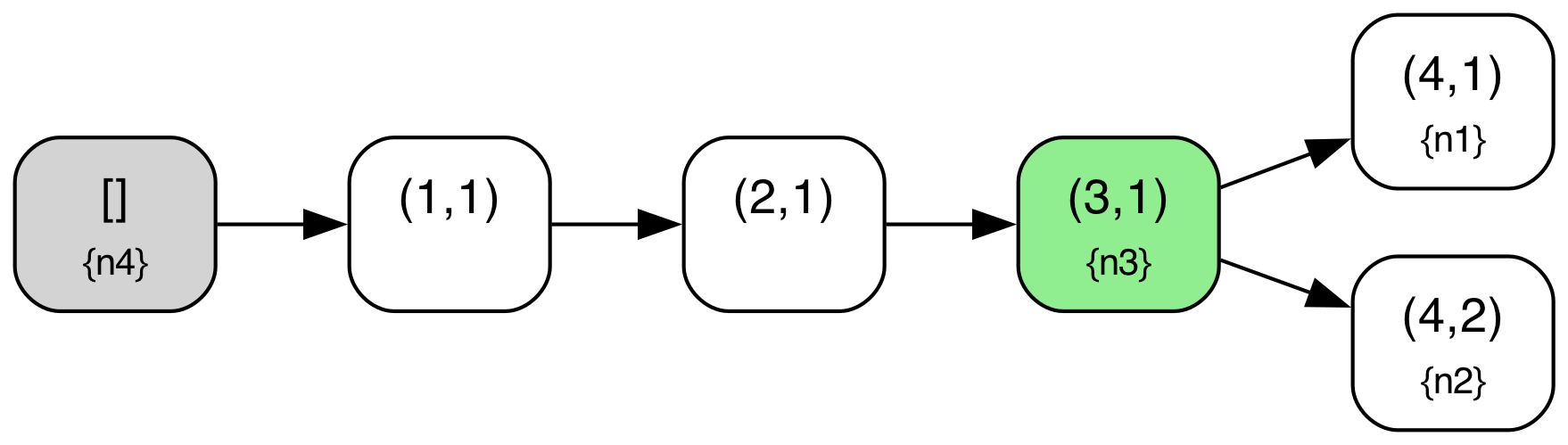

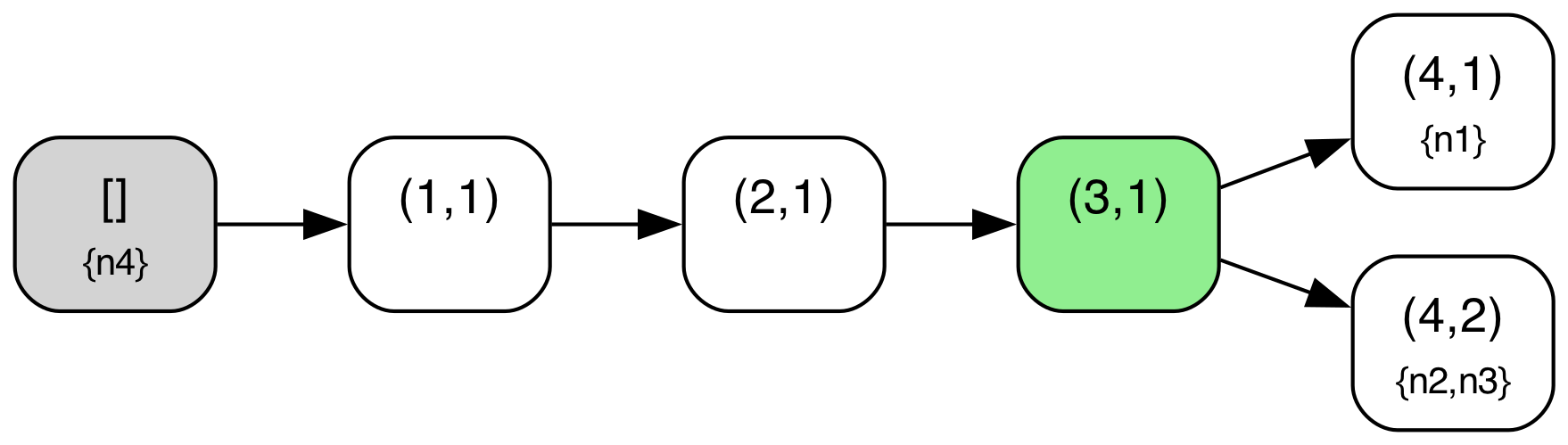

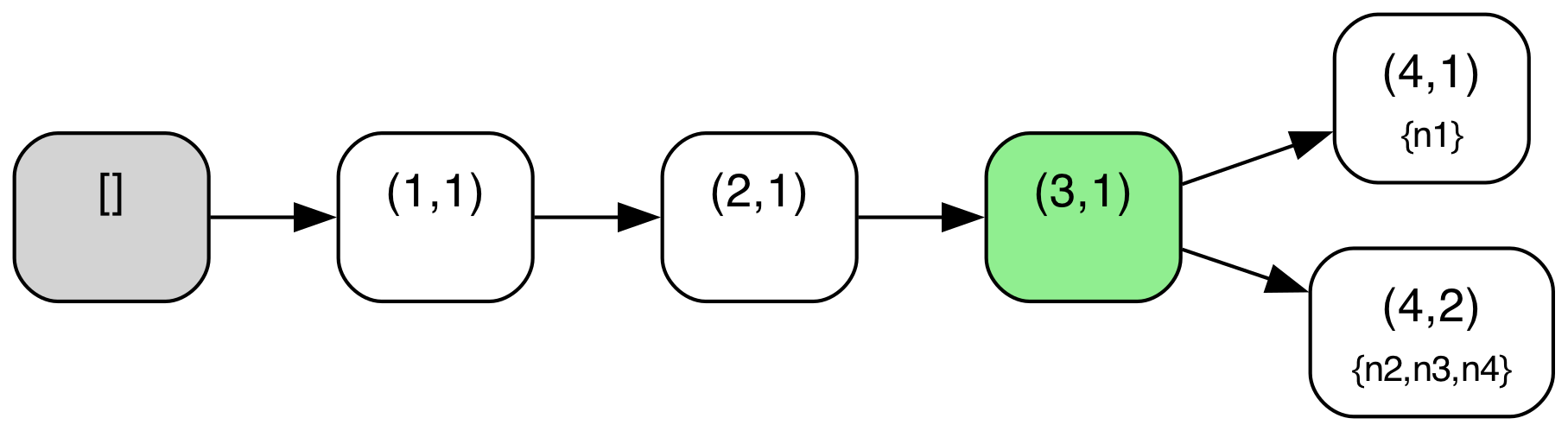

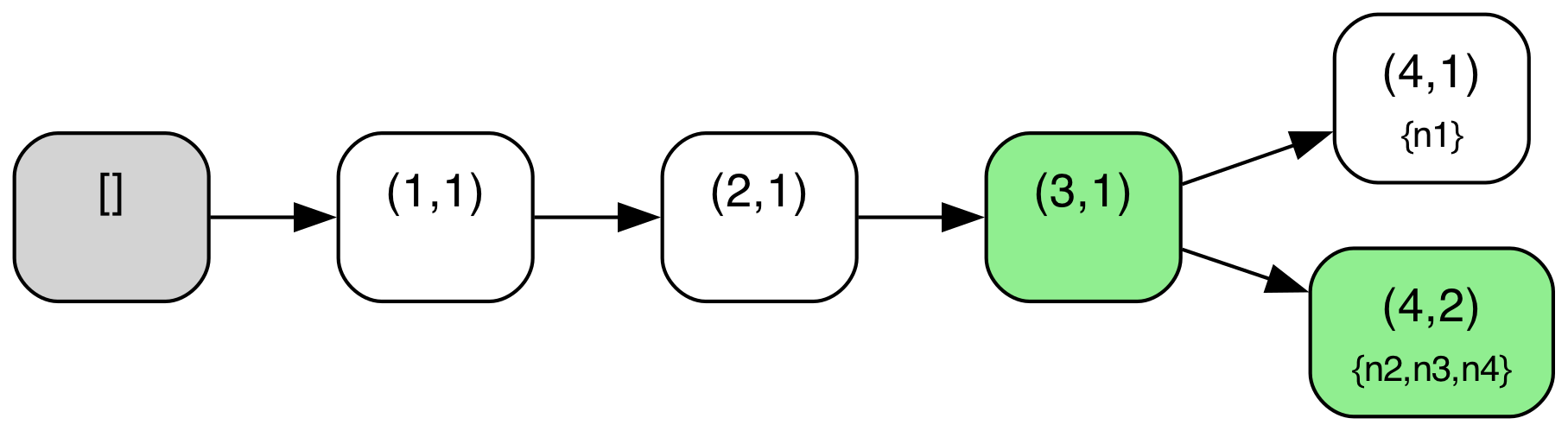

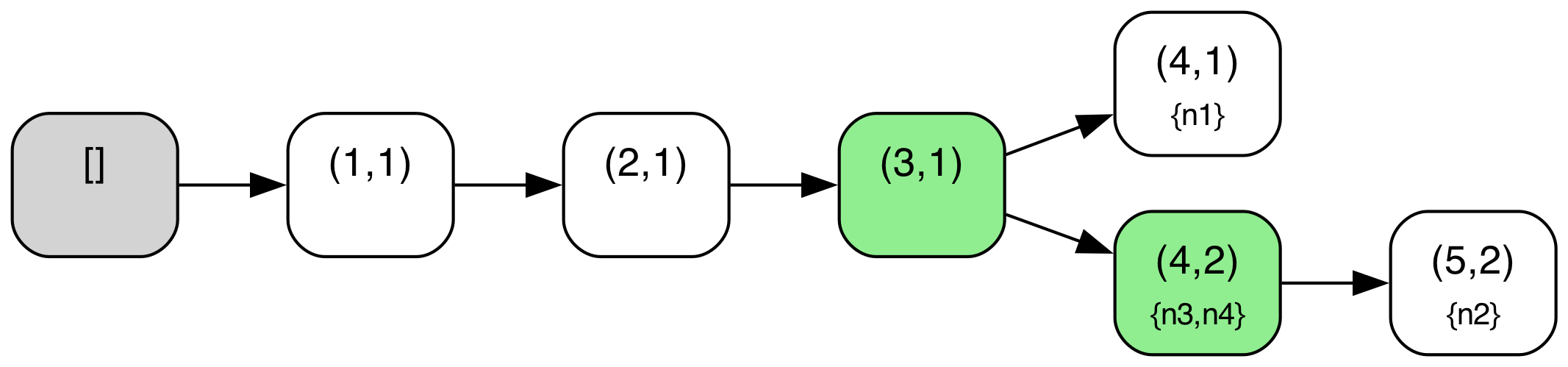

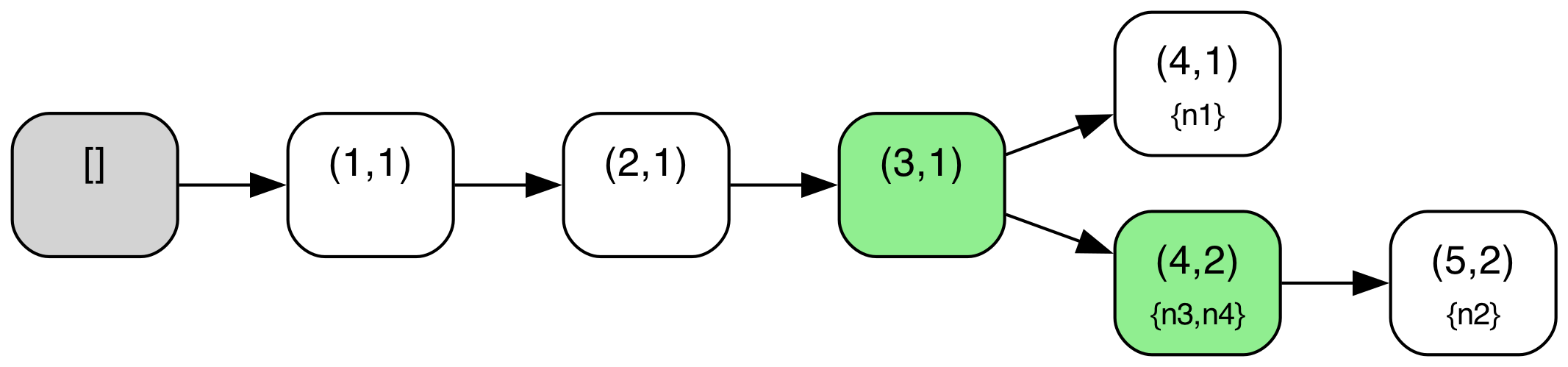

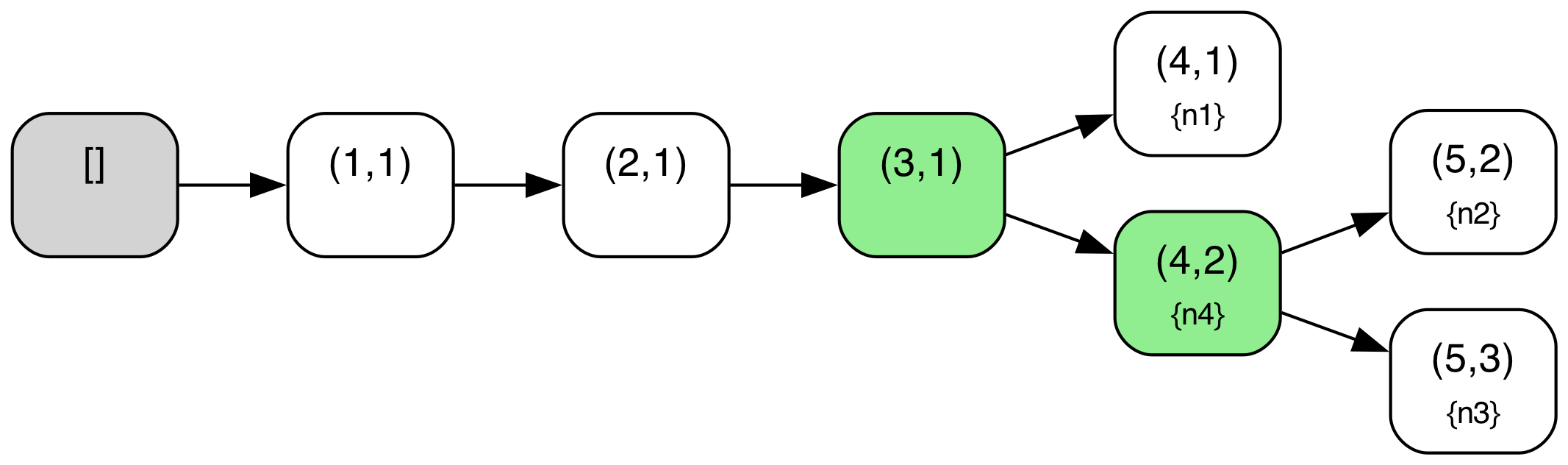

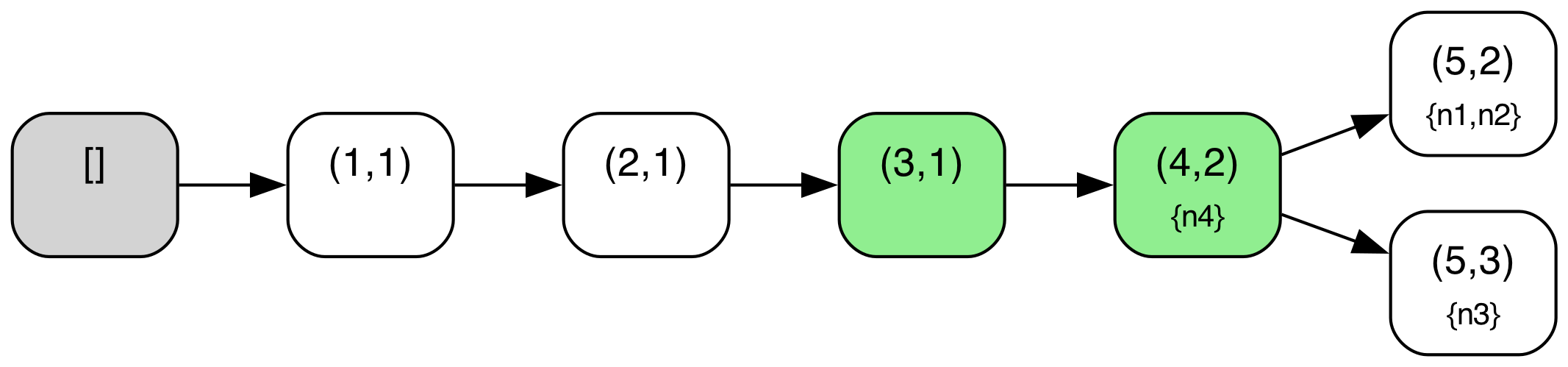

We can illustrate this more concretely if we look at a sample protocol behavior through this lens. The diagram below shows a behavior from the above TLA+ specification of the abstract variant of Raft with a configuration of 4 servers ({n1,n2,n3,n4}). The log tree structure shown is defined where nodes correspond to log entries (i.e. (index,term) pairs) and edges correspond to adjacent log entries in some given log across any node. The log tree is also annotated with each node’s current “position” in the tree i.e. the log entry that corresponds to their current last log entry (nodes with an empty log are simply omitted in those annotations), and entries marked as committed are highlighted in green. A special “root” node in gray denotes an empty log, the initial state for all nodes.

| State 0: Initial State |

|

| State 1: BecomeLeader(n1, ['n1', 'n2', 'n3']) |

|

| State 2: ClientRequest(n1) |

|

| State 3: ClientRequest(n1) |

|

| State 4: ClientRequest(n1) |

|

| State 5: MergeEntries(n2, n1) |

|

| State 6: MergeEntries(n3, n1) |

|

| State 7: CommitEntry(n1, ['n1', 'n2', 'n3']) |

|

| State 8: ClientRequest(n1) |

|

| State 9: BecomeLeader(n2, ['n2', 'n3', 'n4']) |

|

| State 10: ClientRequest(n2) |

|

| State 11: MergeEntries(n3, n2) |

|

| State 12: MergeEntries(n4, n2) |

|

| State 13: CommitEntry(n2, ['n2', 'n3', 'n4']) |

|

| State 14: ClientRequest(n2) |

|

| State 15: BecomeLeader(n3, ['n1', 'n3', 'n4']) |

|

| State 16: ClientRequest(n3) |

|

| State 17: MergeEntries(n1, n2) |

|

When a new leader gets elected, a “fork” may be created in this tree, if the new leader did not contain all previously created (but uncommitted) log entries. For example, this first occurs in State 10, when node n2 has become leader and written a new entry but without the log entry (4,1) created by n1. Similarly, another fork is created when a branch via n3 is created in State 16.

Note also that local log “pointers” move along paths in this tree as new logs are replicated or “merged” around. For example, in State 10 to State 11 transition, n3 replicates the log from n2, and so moves its pointer in the tree ahead to entry (4,2). Note also that due to the key “log matching” property that is maintained in Raft, (index, term) pairs should identify unique prefixes/paths within this tree.

Pruning of branches in this tree also occurs when a node with an old/stale node merges its log with a newer log. In standard Raft, this pruning will also occur, but typically occur in stages e.g. first as a node truncates its log, and then replicates new entries to come into alignment with an up to date branch. For example, in State 17, n1 has merged itself onto the newer branch of n2, pruning its older, stale branch ending in entry (4,1).

This perspective on Raft logs helps to provide intuition on the “merging” strategy we outlined above. Local logs can be seen as views or paths in this global tree structure, and replication of logs between nodes can be viewed as a way of bringing divergent branches back in sync and replicating a branch to a sufficient number of nodes to ensure safe commit. Note that this blog post on chaining in Raft puts forth similar perspectives, partially through the lens of blockchain protocols.

Going Logless

In this abstract, “merging” based variant of the Raft, lower level log management operations have been abstracted away. That is, the entire log is a monolithic piece of state that is replicated around between nodes in one shot, and we only care about some notion of logical “ordering” between two different logs, which is determined by the “last term” ordering condition described above.

In this monolithic log model, we only care about comparison between the end of each log. So, it is relatively straightforward to see that we can view such a protocol as simply storing a “rolled up” log at each node i.e. storing the full piece of state that corresponds to application of all entires in a log, tagged by the “(last index, last term)” of that log. When we propagate around logs, we don’t actually need to store the whole log, but only the state corresponding to application of that log’s entries. And we can easily compare two pieces of this state by simply comparing the tagged index/term values.

From this perspective, we can now imagine a variant of Raft that stores some arbitrary piece of state, which gets updated “in-place” via client operations at a leader node. This state is propagated to followers via messages that contain the entire state, and they decide whether to install the newer state or not based on this simple “merging” logic which does this logical comparison in version between their own local state and the state they received. When we write a new entry down on a leader, we can simply update that state in-place and increment the “index” (perhaps more appropriately, can be called an object “version”) for the local state.

Related Work

There are many other versions of logless or “register” style consensus algorithms. Recent proposals like CASPaxos and RMWPaxos try to do something similar for Paxos-based systems, and there is also a history of literature on “atomic registers”, implementing this type of primitive in a distributed fashion. This post from the author of Bizur also discusses similar ideas.

I haven’t seen this logless variation specifically appear in the context of a Raft-based protocol, though it is essentially similar to the ideas employed in the design of a new reconfiguration protocol within MongoDB’s Raft-based consensus system. It is also somewhat informative to derive this logless variant through a series of relatively straightforward modifications to standard, “log-based” versions of Raft.