Defining Safety and Liveness

Temporal logic properties can be broadly categorized into safety and liveness properties. Informally, safety properties state that a “bad thing” never happens whereas liveness properties state that a “good thing” must eventually happen. These informal definitions are made precise in the paper Defining Liveness (Alpern, Schneider, 1985), and are also discussed in a later paper, Decomposing Properties into Safety and Liveness using Predicate Logic (Schneider, 1987).

Formalizing Safety and Liveness

An execution \(\sigma\), which we can also refer to as a behavior, is as an infinite sequence of states

\[\sigma = s_0,s_1,s_2,...\]A property is a set of such sequences. We write \(\sigma \vDash P\) if execution \(\sigma\) satisfies property \(P\). We can alternately say that \(\sigma\) is contained in \(P\). We denote the set of all infinite executions as \(S^\omega\) and the set of all finite (partial) executions as \(S^*\). Finally, we let \(\sigma_i\) represent the partial execution consisting of the first \(i\) states of an execution \(\sigma\).

We say that a property \(P\) is a safety property if and only if the following holds for all behaviors:

\[(\sigma \nvDash P) \iff \exists i \in \mathbb{N} : (\forall \beta \in S^\omega : \sigma_i\beta \nvDash P)\]This definition says that if a behavior violates a safety property \(P\), then it must do so in some finite prefix of the behavior i.e. the violation occurs at some discrete point. After that point you could try to extend the behavior with any suffix \(\beta\) but you would not be able to remedy the violation. Note that even though a safety property is always violated at a discrete point, it may require looking at an entire behavior prefix to determine whether the property is violated. Invariants are a class of safety property whose truth can be determined by looking at a single state of a behavior e.g. “x is never equal to 0”. There are other safety properties, however, where this is not the case. For example, to determine the truth of a property “if x=0 then x=1 three steps later” we must examine multiple states of a behavior.

Intuitively, we can think about a safety property as one which rules out “bad” prefixes. It only includes behaviors where all prefixes are “safe”, where a safe prefix is one that can be extended to satisfy \(P\). We can formalize this intuition by looking at the contrapositive of the definition given above:

\[\begin{aligned} \neg(\exists i \in \mathbb{N} : (\forall \beta \in S^\omega : \sigma_i\beta \nvDash P)) &\iff \neg(\sigma \nvDash P) \\ \end{aligned}\]We can simplify this formula to derive an alternate, equivalent form of the definition:

\[\begin{aligned} \neg(\exists i \in \mathbb{N} : (\forall \beta \in S^\omega : \sigma_i\beta \nvDash P)) &\iff \sigma \vDash P \\ (\forall i \in \mathbb{N} : \neg(\forall \beta \in S^\omega : \sigma_i\beta \nvDash P)) &\iff \sigma \vDash P \\ (\forall i \in \mathbb{N} : (\exists \beta \in S^\omega : \neg(\sigma_i\beta \nvDash P)) &\iff \sigma \vDash P \\ (\forall i \in \mathbb{N} : (\exists \beta \in S^\omega : \sigma_i\beta \vDash P)) &\iff \sigma \vDash P \end{aligned}\]If we swap the order of the final statement we get:

\[\sigma \vDash P \iff \forall i \in \mathbb{N} : (\exists \beta \in S^\omega : \sigma_i\beta \vDash P)\]which captures the intuition that a safety property \(P\) is one where the behaviors in \(P\) are exactly those with safe prefixes.

We say that a property \(P\) is a liveness property if and only if the following holds:

\[\forall \alpha \in S^* : (\exists \beta \in S^\omega : \alpha \beta \vDash P)\]This definition says that a property \(P\) is a liveness property if any partial execution \(\alpha\) can be extended to satisfy \(P\). That is, no matter how many finite steps we take in a behavior prefix, there’s always hope that we can satisfy a liveness property in the future (“while there’s life there’s hope”). Note that the “good thing” required by a liveness property may or may not be discrete. A simple liveness requirement like “x is eventually 0” will be satisfied at a discrete point in a behavior, but a liveness condition like “x is 0 infinitely often” can only be determined by examining an infinite behavior. One consequence of this definition is that any liveness property must contain all finite prefixes. Defining a particular liveness property is a matter of determining which extensions of these finite prefixes to include.

The Decomposition Theorem

It turns out that any property can be written as a conjunction of a safety and liveness property. This theorem is proven in Defining Liveness by resorting to a topological characterization of safety and liveness properties, defining a topology where safety properties are the closed sets and liveness properties are the dense sets. In that paper, they decompose an arbitrary property \(P\) as

\[P = \overline{P} \cap L\]where \(\overline{P}\) is the smallest safety property that contains \(P\), and \(L=\neg(\overline{P}-P)\).The topological characterization of safety and liveness properties is not the best way for me understand the topic at first since I don’t have a strong prior intuition in topology. We can prove the theorem without resorting to the topological characterization, though.

The safety property \(\overline{P}\) consists of all behaviors with only “safe” finite prefixes. Formally, we can say that a given behavior \(\sigma\) is safe with respect to property \(P\) if all finite prefixes of \(\sigma\) can be extended to satisfy \(P\) i.e.

\[Safe_P(\sigma) = \forall i \in \mathbb{N} : \exists \beta \in S^\omega : \sigma_i\beta \vDash P\]\(\overline{P}\) is the set of all behaviors \(\sigma\) that satisfy \(Safe_P(\sigma)\). Note that this set may be larger than \(P\), since it is possible that \(\sigma \nvDash P \wedge Safe_P(\sigma)\). For example, consider the property “x=0 initially and eventually x=1”. The behavior where x=0 in every state is clearly safe but it still violates the property. The behaviors that satisfy \(Safe_P(\sigma)\) but not \(P\) are exactly those in \(\overline{P}-P\). We want to intersect \(\overline{P}\) with a liveness property \(L\) that will get rid of the behaviors in \(\overline{P}-P\), leaving us with only the behaviors in \(P\). It turns out that we can take \(L\) to be the set of all behaviors except for those in \(\overline{P}-P\). That is, \(L=\neg(\overline{P}-P)\).

We can see how the intersection of these properties gives us \(P\):

\[\begin{aligned} \overline{P} \cap L &= \overline{P} \cap \neg(\overline{P} - P) \\ &= \overline{P} \cap \neg (\overline{P} \cap \neg P) \\ &= \overline{P} \cap (\neg \overline{P} \cup P ) \\ &= (\overline{P} \cap \neg \overline{P}) \cup (\overline{P} \cap P) \\ &= \emptyset \cup P \\ &= P \\ \end{aligned}\]As a side note, in some of these formulas and derivations we go back and forth between expressing properties in logical formulas and in set notation, which may be confusing, but it’s helpful to remember the correspondences between common set and logical operations. For example, set intersection (\(\cap\)) corresponds to logical conjunction (\(\wedge\)), set union (\(\cup\)) corresponds to logical disjunction (\(\vee\)), and negation (\(\neg\)) corresponds to set complement. This arises from the fact that we can think about properties either as logical formulas or sets of behaviors.

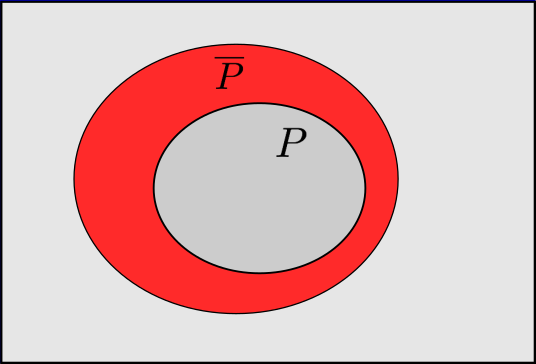

It can also be helpful to understand how these set operations work by looking at a diagram. In the image below, the outer rectangle represents the space of all behaviors, the gray region represents \(L=\neg(\overline{P}-P)\), and the red region represents \(\overline{P}-P\). The larger oval contains the behaviors in \(\overline{P}\) and the smaller oval contains the behaviors in \(P\).

It remains to show that \(L\) is actually a liveness property. We can assume that \(L\) is not a liveness property and derive a contradiction. If \(L\) is not a liveness property it means there exists some finite execution \(\sigma \in S^*\) such that no extension of \(\sigma\) satisfies \(L\). So it must be the case that no behaviors in \(L=\neg(\overline{P} - P)\) have \(\sigma\) as a prefix, since this would mean there exists some extension of \(\sigma\) that satisfies \(L\). Since \(\neg(\overline{P} - P)\) and \(\overline{P} - P\) partition the space of all behaviors (one is the complement of the other), and no behavior in \(\neg(\overline{P} - P)\) contains the prefix \(\sigma\), it must mean that some behavior in \(\overline{P} - P\) contains the prefix \(\sigma\). By definition, though, we know that the prefixes in \(\overline{P} - P\) are exactly those that have an extension in \(P\) i.e. they are all safe prefixes. So, if \(\sigma \in \overline{P}-P\) there must be an extension of \(\sigma\) in \(P\). Since \(P\) is a subset of \(L\), this implies that there is an extension of \(\sigma\) in \(L\), which violates our initial assumption that there is no extension of \(\sigma\) in \(L\). Therefore, \(L\) must be a liveness property.

Here is another way to think about the proof of the safety-liveness decomposition. To construct an arbitrary property \(P\), we start by picking out all the safe prefixes, which gives us our safety property \(\overline{P}\). This leaves us with a set of behaviors that are safe but may still violate our property. The set \(\overline{P}-P\) from above is the subset of behaviors that still violate \(P\). We need a liveness property \(L\) to fix this. As we noted above, by definition any liveness property must include all finite prefixes, whether they are safe or not, so we have no choice but to include all prefixes in \(L\). The simplest liveness property we could start with is the one that includes all behaviors, but this will obviously not work since it will include the behaviors in \(\overline{P}-P\) i.e. the behaviors that are safe but violate \(P\). Ideally, we would want to remove from \(L\) exactly the behaviors in \(\overline{P}-P\). The question, though, is after removing them will we still have a liveness property? As we noted, all finite prefixes must be contained in a liveness property, so we can remove individual behaviors from \(L\) but we cannot remove so many behaviors such that a particular finite prefix is no longer contained in the liveness property. Remember that the liveness definition only specifies that every partial execution has some extension in \(L\). It doesn’t care how many there are. So, if we remove all the behaviors in \(\overline{P}-P\) from \(L\), will \(L\) still be a liveness property? Well, the prefixes contained in \(\overline{P}-P\) are all safe prefixes, by definition, and we know that all of these prefixes must also appear in \(P\), since \(P\) will contain all of the safe prefixes. So, removing all the behaviors from \(\overline{P}-P\) from our liveness property doesn’t change the set of prefixes contained in \(L\), so it will still be a liveness property, and we know that its intersection with our safety property gives us exactly \(P\).

Note that I got some inspiration for the above explanations from this short lecture on safety and liveness.

Liveness-Liveness Decomposition

At a high level, the safety liveness decomposition feels somewhat natural, since it reflects the way we often think about the behavior of real systems. It turns out, however, that it is also possible to express any property \(P\) as the conjunction of two liveness properties. This is an additional theorem given in Defining Liveness. If \(S\) is the set of all states, and \(\mid {S} \mid > 1\) (i.e. there are at least 2 possible system states), then we let \(L_a\) be the set of all executions with tails that are infinite sequences of \(a\)’s and \(L_b\), similarly, be the set of sequences with infinite tails consisting of \(b\)’s. The intersection of \((P \cup L_a)\) and \((P \cup L_b\)) (which both happen to be liveness properties) gives us \(P\). I don’t have a good intuition for why this decomposition works yet and I’m not sure if it has any notable theoretical or practical significance, but I found it to be an interesting auxiliary result.