Modern Views of Transaction Isolation

There have been many attempts to formalize the zoo of various transaction isolation and consistency concepts over the years. It is not always clear, though, to what extent these attempts have clarified things, especially when each approach has introduced new variations of complexity and formal notation. The rise of distributed storage and database systems and the need to reason about isolation in these contexts has likely worsened the situation.

There are a host of proposed formalisms that all approach the problem from different angles, with different frameworks, notations, etc. (Adya, Cerone, Crooks). They are all quite dense and differ in nontrivial ways, so it is helpful to try to understand some of the common underlying concepts between them. In particular there are two “modern” (post Adya 1999) formalisms of isolation, Cerone 2015 and Crooks 2017, which take a similar “read-centric” view of isolation. Their surface details and formalizations appear quite different, but they share many similarities in their core ideas.

Modern Isolation Formalisms

A unifying concept of essentially any transaction isolation formalism is that an isolation definition can be viewed as a condition over a set of committed transactions. That is, given some set of transactions that were committed by a database system, these transactions either satisfy a given isolation level or not, based on the sequence of read and write operations present in each of these transactions.

Note that a core aspect of any formal isolation definition is about putting conditions on how reads observe database state. If we have a set of transactions that only perform writes, we might have some intuitive correctness notion for how a database should execute these transactions, but we can’t make such a definition formal unless there exist some read operations that may observe the effect of other transaction’s writes. So, we can say that, to a first degree, a transaction isolation definition should be about conditions on the set of values that a transaction can read. The modern models of 2015 model of Cerone et al. and the subsequent Crooks 2017 client-centric model both approach isolation in a somewhat similar, “read-centric” view.

Under this “read-centric” view, when we think about how to define an isolation level, we should first be concerned with how we define what values a transaction can read. If our isolation level makes no restrictions on this, then a transaction can read any value (in practice how you might define a level like read uncommitted). More sensibly, we would expect a transaction to read states that are reasonable, in some sense. More concretely, we should expect transactions to actually read values written by other transactions. This could be a starting definition for isolation (similar to read committed), and one step up in strength from allowing transactions to read any possible value.

There are some other reasonable constraints, though. Basically, we likely expect that the possible states we read from came about through some “reasonable” execution of the transactions we gave to the database. One “reasonable” type of execution would be to execute these transactions in some sequential order. This is, for example, what we would expect out of a database system if we gave it a series of transactions one-by-one, with no concurrent overlapping between transactions (e.g. the classic notion of serializability). The Cerone and Crooks model both allow for a more precise formalization of these ideas.

Cerone 2015

The Cerone paper, A Framework for Transactional Consistency Models with Atomic Visibility, starts with a core simplifying assumption of atomic visibility, which is that either all or none of the operations of a transaction can become visible to other transactions. This means that their model cannot represent isolation levels like Read Committed, which is weaker than Read Atomic, the weakest level their model can express.

Their model encodes the intuitive idea of “read-centric” isolation by first defining a visibility relation between transactions i.e. a way of defining which transactions are visible to other transactions. That is, if a transaction reads a key, what other transaction writes should it observe. It defines this in terms of abstract executions, where an abstract execution consists of a set of committed transactions (called a history \(\mathcal{H}\)) along with two relations over this set:

- Visibility (\(\mathsf{VIS} \subseteq \mathcal{H} \times \mathcal{H}\)): acyclic relation where \(T \overset{\mathsf{VIS}}{\rightarrow} S\) means that \(S\) is aware of \(T\).

- Arbitration (\(\mathsf{AR} \subseteq \mathcal{H} \times \mathcal{H}\)): total order such that \(\mathsf{AR} \supseteq \mathsf{VIS}\) where \(T \overset{\mathsf{AR}}{\rightarrow} S\) means that the writes of \(S\) supersede those written by \(T\) (essentially only orders write by concurrent transactions).

Basically, \(\mathsf{VIS}\) is a partial ordering of transactions in a history, and \(\mathsf{AR}\) is a total order on transactions that is a superset of \(\mathsf{VIS}\) (i.e. any edge in \(\mathsf{VIS}\) is also by default an edge in \(\mathsf{AR}\)). Note that \(\mathsf{AR}\) is a total order, so every two transactions are comparable by this ordering even if, in some cases (as discussed below), this ordering is not relevant, and could be omitted.

A consistency model (e.g. isolation level) is then defined as a set of consistency axioms constraining executions, where a consistency model allows histories for which there exists an abstract execution satisfying the axioms. In other words, given a set of transactions that executed against the database, they satisfy a consistency/isolation level if there exists an abstract execution that obeys the axioms of that consistency/isolation level, meaning that there exists a \(\mathsf{VIS}\) and \(\mathsf{AR}\) relation over this set that satisfies the axioms.

The weakest isolation level defined in the Cerone model, Read Atomic, imposes only two conditions: internal and external consistency, which are defined intuitively as:

- \(I\small{NT}\) (internal consistency): reads from an object returns the same value as the last write to or read from this object in the transaction.

- \(E\small{XT}\) (external consistency): the value returned by an external read in \(T\) is determined by the transactions \(\mathsf{VIS}\)-preceding \(T\) that write to \(x\). If there are no such transactions, then \(T\) reads the initial value 0. Otherwise it reads the final value written by the last such transaction in \(\mathsf{AR}\).

Internal consistency is a bit tedious from a formal perspective and is the less interesting condition, stating essentially that you read your own writes within a transaction. External consistency is the more important condition and depends on the visibility relation, stating that a transaction will read the value written by the latest transaction preceding it in the visibility relation, with conflicts decided by the arbitration relation. Note that if the read and write sets of two transactions are disjoint, then visibility relation is kind of irrelevant for them, so it doesn’t matter whether such an edge is or isn’t included in \(\mathsf{VIS}\).

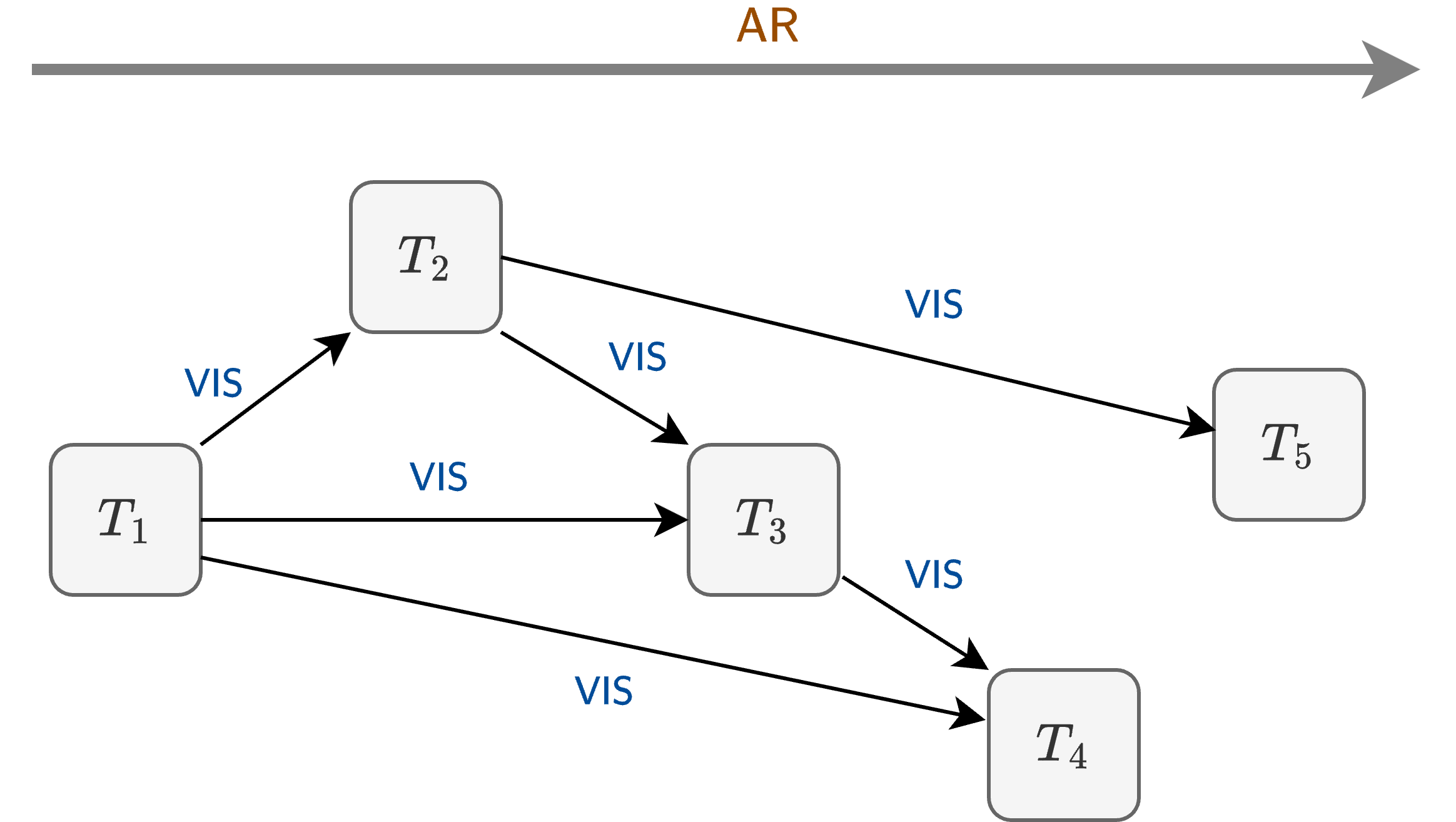

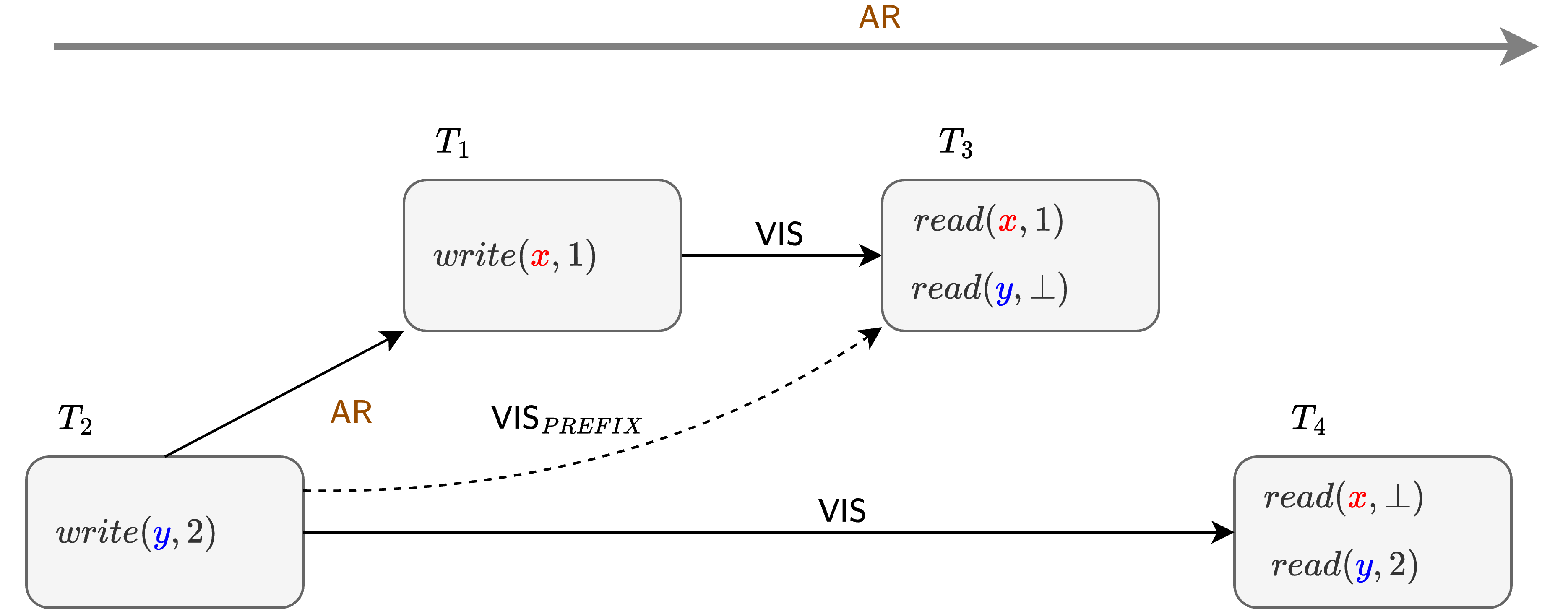

So, at this weakest defined isolation level, Read Atomic, we can think about a whole batch of committed transactions, and the only restrictions that we are placing on their reads is that they observe the effects of some other transaction(s) in this set, determined by the transaction’s incoming visibility (\(\mathsf{VIS}\)) edges (e.g. as illustrated in Figure 1). If multiple transactions among the incoming visibility edges wrote to conflicting key sets, then the \(\mathsf{AR}\) exists to arbitrate between them, determining which write is observed. Note also that \(\mathsf{AR}\) is a total order, so we can think about (and visualize) it as a global, linear ordering of all transactions, as illustrated by the left-to-right ordering in Figure 1. In some cases this total ordering is not relevant to the semantics of transactions, but we can imagine that it always exists in the background. Also, note that \(\mathsf{AR}\) is a superset of \(\mathsf{VIS}\), so this means you can’t have a visibility edge that goes “backwards” in this arbitration total order.

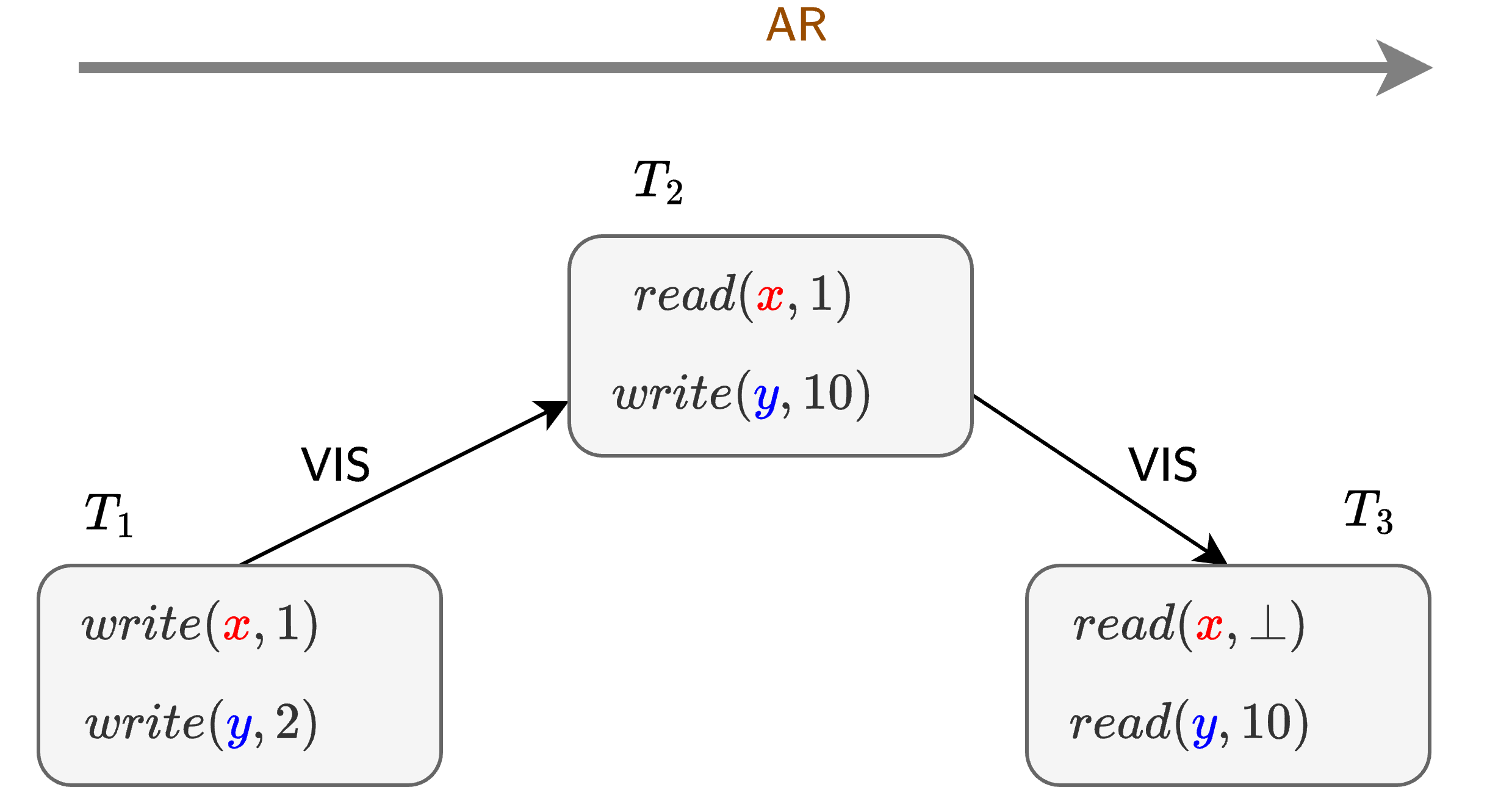

The underlying model requires that the visibility relation is acyclic, but without any other restrictions there are still some unintuitive semantics allowed at this weakest definition, with causality violations as the notable example. Basically, the visibility relation is not, by default, required to be transitive at Read Atomic, so you can end up with transactions observing the effects of some other transaction that observed the effect of an “earlier” transaction, but you don’t observe the effects of the “earlier” transaction e.g. as shown by example below with 3 transactions (i.e. \(T_3\) observes the effect of \(T_2\) via \(y\), and \(T_2\) observes the effect of \(T_1\) via \(x\), but \(T_3\) does not observe the effect of \(T_1\)’s write to \(x\)).

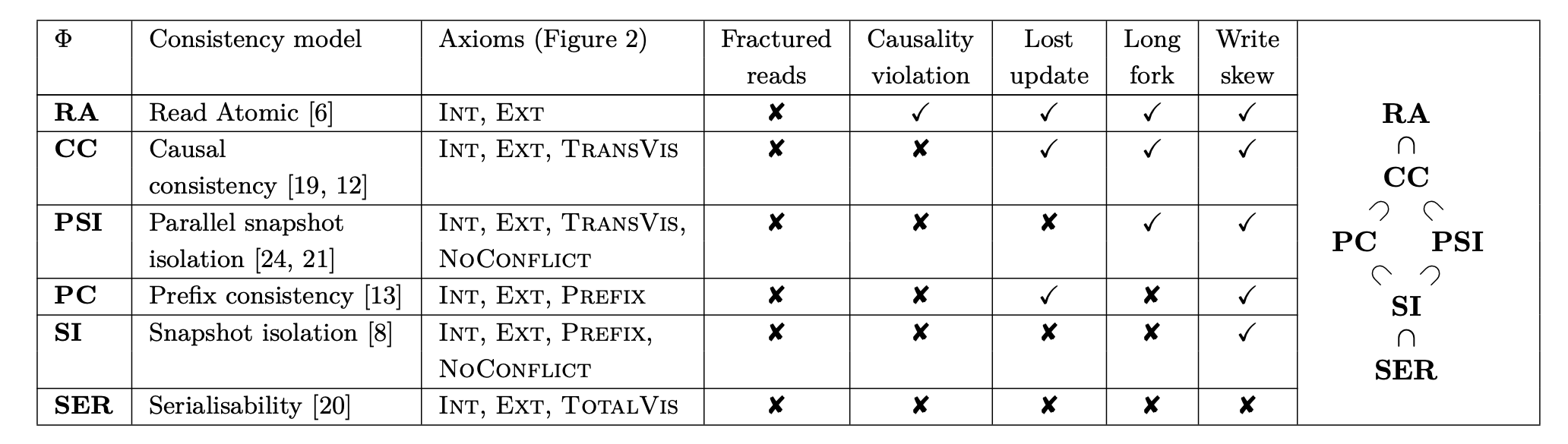

Moving up the isolation hierarchy from Read Atomic in Cerone’s model, we start strengthening requirements on what the reads in transactions can observe. In their framework, this starts by first adding a transitivity condition on visibility (\(T{\small{RANS}}V{\small{IS}}\)), to get Causal Consistency. This is then extended to Parallel Snapshot Isolation (PSI) and Prefix Consistency, two levels that are not strictly comparable to each other in the hierarchy (see Figure 2).

Note that the \(N{\small{O}}C{\small{ONFLICT}}\) condition enforced at PSI is the first condition that is not related to the values observed by reads. Rather, it places conditions on valid cases of conflicting writes between transactions.

Similarly, there is a notable transition from PSI to Prefix Consistency in this hierarchy, which is related to a switch from a partial to total ordering requirements on the visibility relation. Basically, the \(P\small{REFIX}\) condition requires that if \(T\) observes \(S\), then it also observes all \(\mathsf{AR}\) predecessors of \(S\). In the example below, which illustrates the long fork anomaly of PSI, transactions \(T_3\) and \(T_4\) can be understood as observing the effects of \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) in “different orders” i.e. for \(T_3\) it appears as if \(T_1 \rightarrow T_2\), but for \(T_4\) it observed \(T_2 \rightarrow T_1\).

Under the \(P\small{REFIX}\) condition, the arbitration ordering of \(\mathsf{AR}\) between \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) comes into play, effectively enforcing a fixed order on how \(T_1\) and \(T_2\) are observed by other transactions. That is, in the above example, if \(T_3\) observes \(T_1\), then by \(P\small{REFIX}\) it must observe its \(AR\) predecessor \(T_2\). Similarly, \(T_4\) is then only required to observe \(T_2\), conforming to the \(T_2 \rightarrow T_1\) ordering enforced by \(AR\). Recall that since \(AR\) is a total order, this condition is basically saying that if you are ever going to observe some transaction out of some transaction set, then you are also forced to observe all transactions in this set in a fixed order, decided by the arbitration ordering. So, this effectively forces visibility to be totally ordered for concurrent transactions.

If we move all the way to serializability, the conditions are strengthened to \(T{\small{OTAL}}V{\small{IS}}\), requiring simply that \(VIS\) is a total order (along with \(I\small{NT}\) and \(E\small{XT}\) conditions). If we look at A Critique of Snapshot Isolation, though, this offers another approach to formalizing serializability. That is, we instead alter snapshot isolation to prevent read-write conflicts instead of write-write conflicts i.e. if a transaction’s read set is written to by a concurrent transaction, then we must abort it. This is an alternative way to formalize serializability that mirrors more closely the \(N{\small{O}}C{\small{ONFLICT}}\) strengthening added for snapshot isolation levels.

Note that the Read Atomic isolation model (the weakest expressed in the Cerone formalism) can be viewed as an interesting “boundary” in isolation strength since, for something weaker like Read Committed, you only need to ensure that reads within a transaction of a key \(k\) read the value written by some other transaction to key \(k\). At such a weak level, there is no restriction on reading from a “consistent” state across keys. So, the weakest interpretation of read committed might be simply that any read can read any value that was written to that key at some point by any transaction in the history. This may not even impose any notion of ordering on transactions, since you really only care about your consistency guarantees at the level of a single key.

The Read Atomic model was first discussed in Bailis’ 2014 paper on RAMP transactions. Note that Read Atomic can be viewed as similar to Snapshot Isolation but with an allowance for concurrent updates (i.e. it does not prevent write-write conflicts). This was also preceded by their earlier proposal of Monotonic Atomic View (MAV) isolation which is strictly weaker than Read Atomic. Essentially, MAV ensures that you always observe all effects of a transaction, but doesn’t require that reads necessarily read from the same, fixed database snapshot (i.e. it is stronger than Read Committed but weaker than Read Atomic).

Crooks 2017

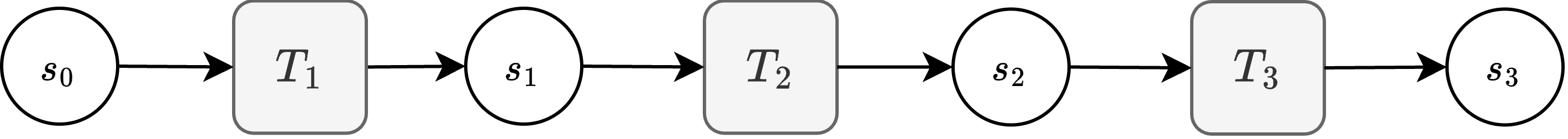

While the Cerone 2015 formalization starts with the visibility and arbitration ordering concepts, the Crooks formalism, presented in Seeing is Believing: A Client-Centric Specification of Database Isolation, takes a different starting point, though there are underlying similarities. Crooks similarly defines isolation over a set of committed transactions, but formalizes its definitions in terms of executions, which are simply a totally ordered sequence of these transactions.

The basic idea of Crooks’ formalism is centered on a state-based or client-centric view of isolation. That is, the values observed by any transactions will be determined based on read states, which are the states that the database passed through as it executed the transactions according to the execution ordering you defined. In a sense, this is similar to the notion of serializability as classically defined i.e. the values observed by each transaction being consistent with some sequential execution ordering that could have occurred.

This is ultimately quite similar to the Cerone view, since the visibility relation (\(\mathsf{VIS}\)) serves a similar purpose i.e. by basically picking out which transactions writes are visible to you. Cerone doesn’t formulate this in terms of “read states” as Crooks does, but essentially the same idea is present i.e. the “read state” in the Cerone model is created by the application of your \(\mathsf{VIS}\)-preceding transactions.

Crooks does also have a technical difference from the Cerone model, in that it allows expression of weaker models like Read Committed, since it does not make the assumption of atomic visibility that Cerone does. It does this by allowing each read operation of a transaction to potentially read from a different read state, allowing for expression of the fractured reads anomaly the Cerone cannot represent.

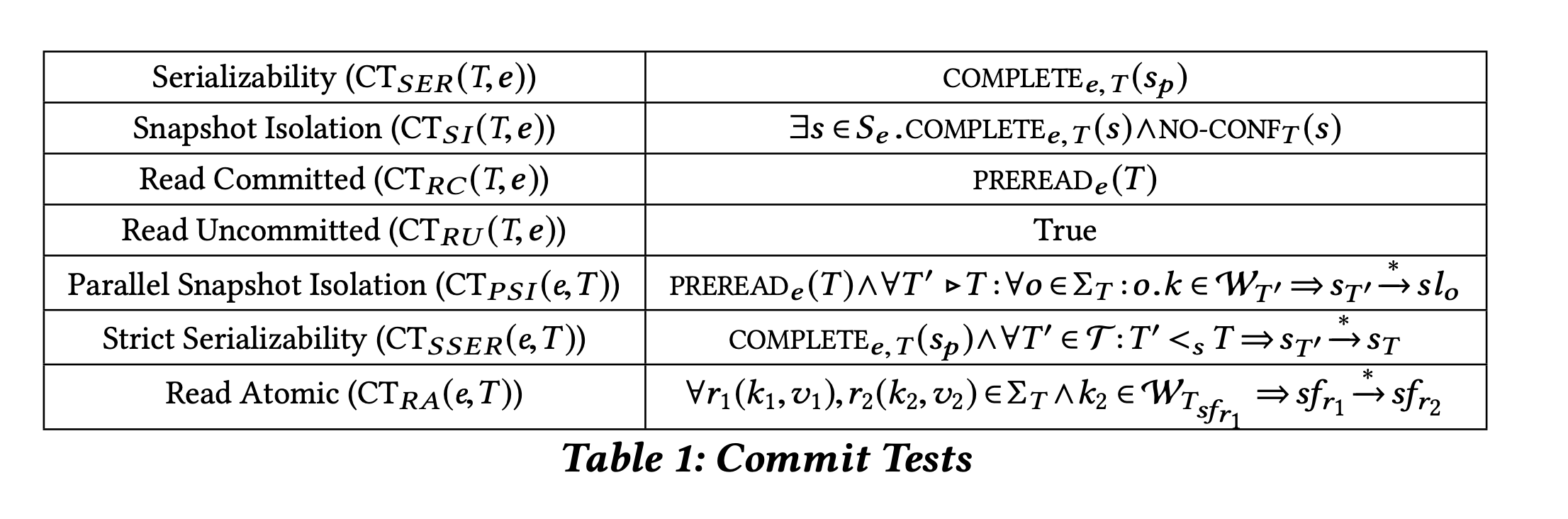

Crooks is also naturally able to represent Read Atomic, though. The formal definition (as shown in Figure 3) is somewhat dense (note that \(sf_o\) represents the first read state for an operation \(o\)), but intuitively it is saying that if an operation \(o\) observes the writes of a transaction \(T_i\), all subsequent operations reading a key in \(T_i\)’s write set must read from a state that include \(T_i\)’s effects.

While Crooks and Cerone models are kind of different on the surface and in their formal details, they can be viewed as quite similar in their core ideas, which are about first establishing what possible values a transaction can read. We can roughly map Cerone’s model to Crooks’ model as well. We can consider the \(\mathsf{AR}\) total order of Cerone as analogous to the “execution order” used in the Crooks model, which is also a total order of transactions. The \(\mathsf{VIS}\) relation of Cerone is then akin to the selection of read states in Crooks’ model. That is, each transaction in the chosen total order picks out some transactions that are visible to it, and reads values accordingly. In Crooks’ model, based on the read state you pick, the transactions visible to you (as in Cerone) would be determined by the transactions preceding that read state.