1 Temporal Logic Model Checking

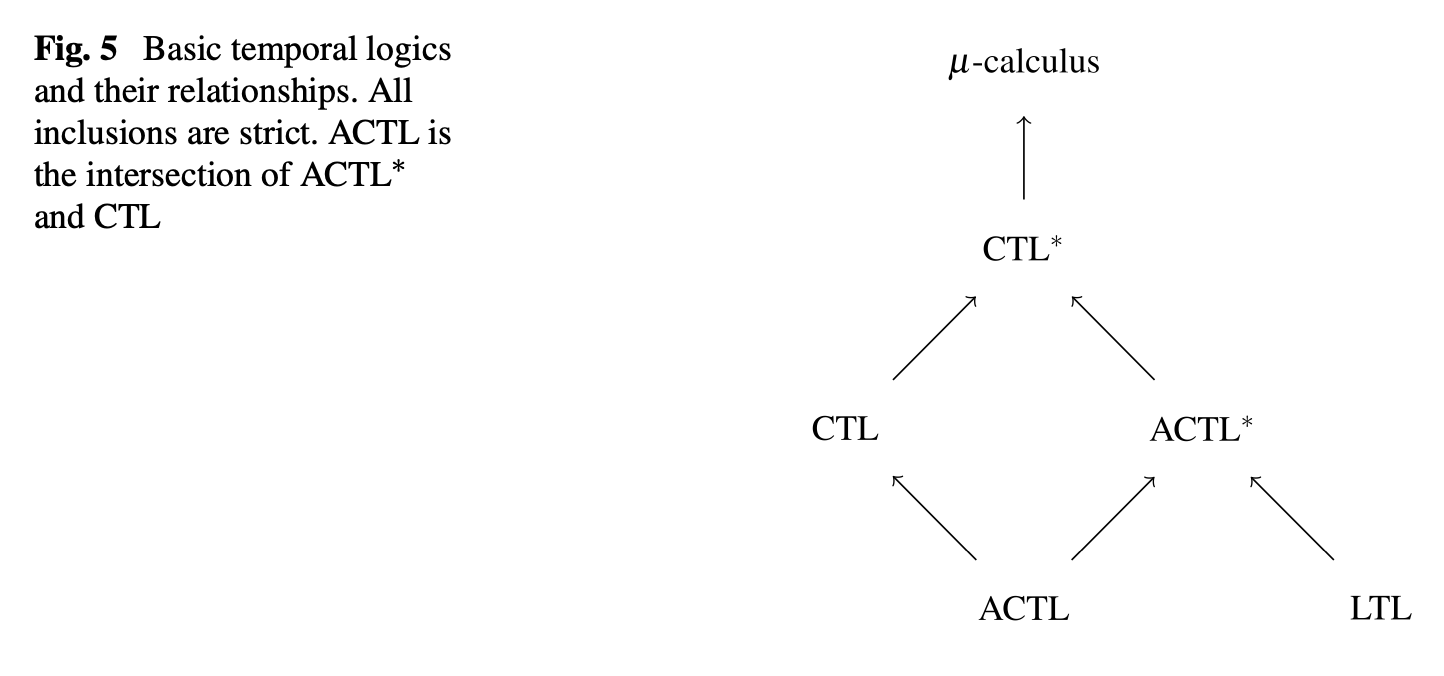

There are a variety of temporal logics that have been used to reason about properties of programs/systems. A high level overview is shown in the relationship diagram below, where CTL* is one of the most expressive logics (encompassing both CTL and LTL).

In practice, I don’t think it’s that important to worry much about the finer distinctions between the various logics, since typically I am more concerned with how to express a desired correctness property (e.g. for which LTL may often be sufficient). Nevertheless, it is good to have a general view of the classification hierarchy to understand the landscape (and since various papers may choose to express/formalize things in different choices of logics).

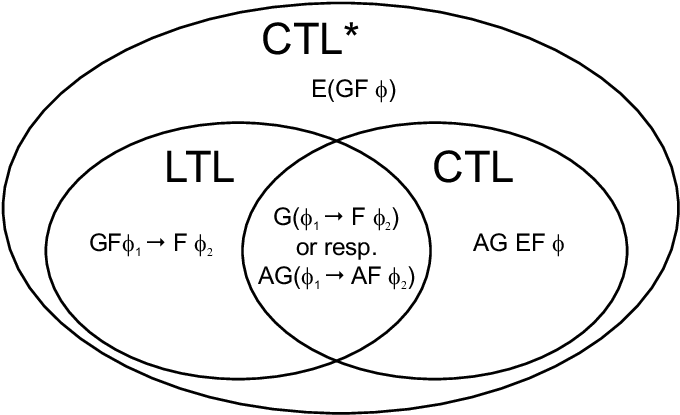

The below diagram also shows the relationship between LTL, CTL, and CTL*. Namely, that LTL and CTL are not directly comparable, and CTL* subsumes them both.

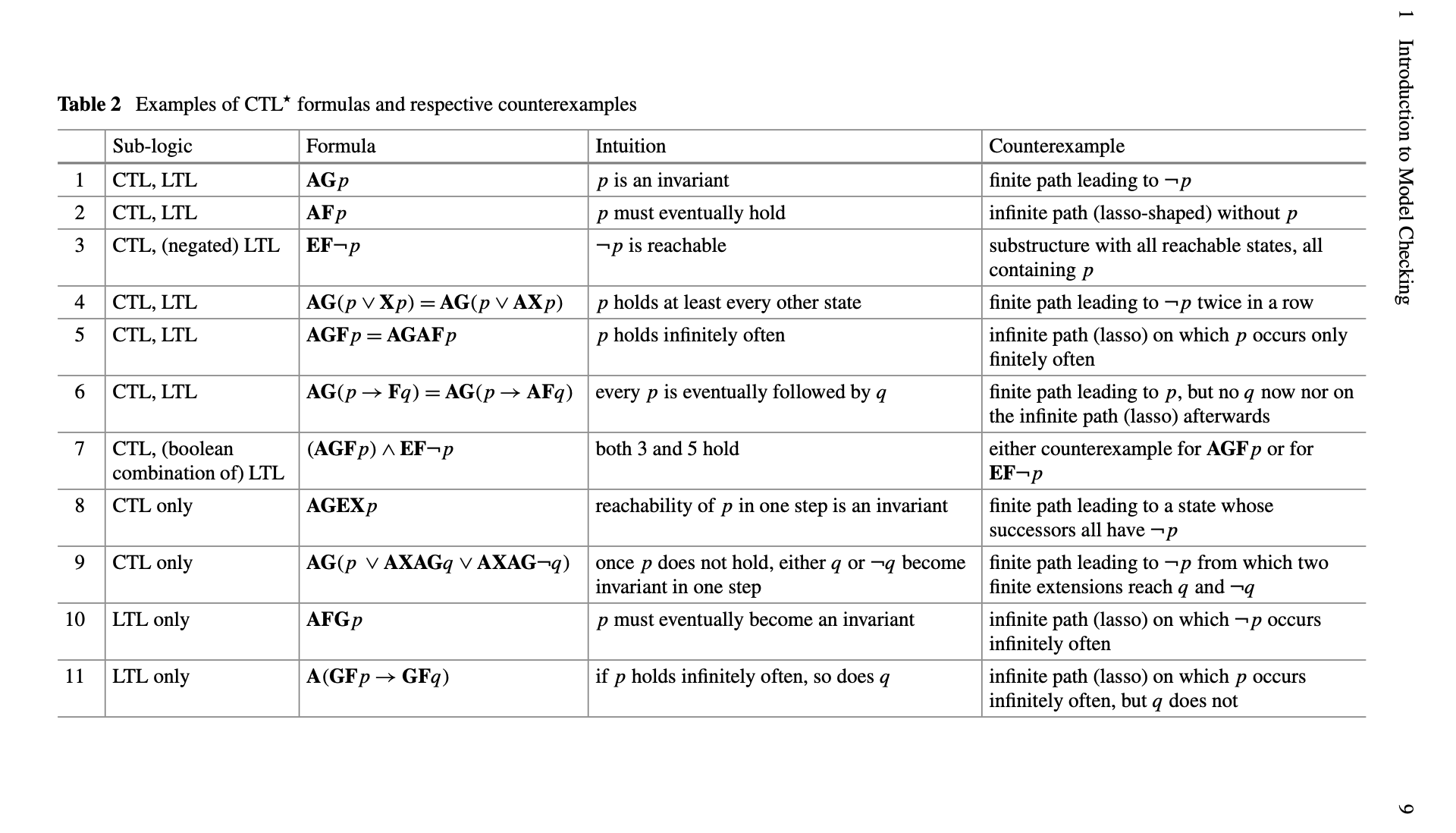

The following diagram (Edmund M. Clarke, Henzinger, and Veith 2018) also provides a good overview of common varieties of temporal logic properties and their counterexample characterizations.

CTL Model Checking

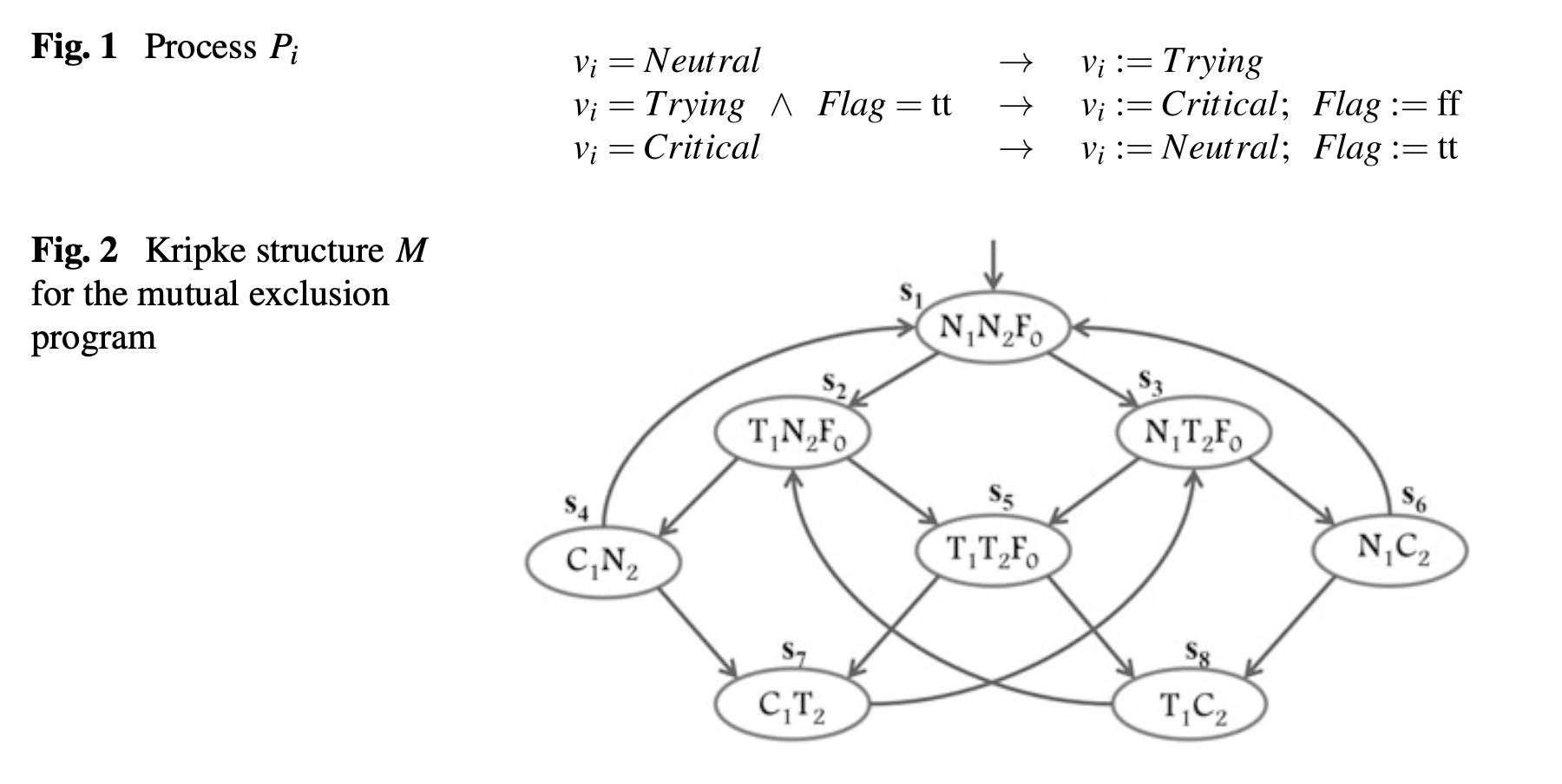

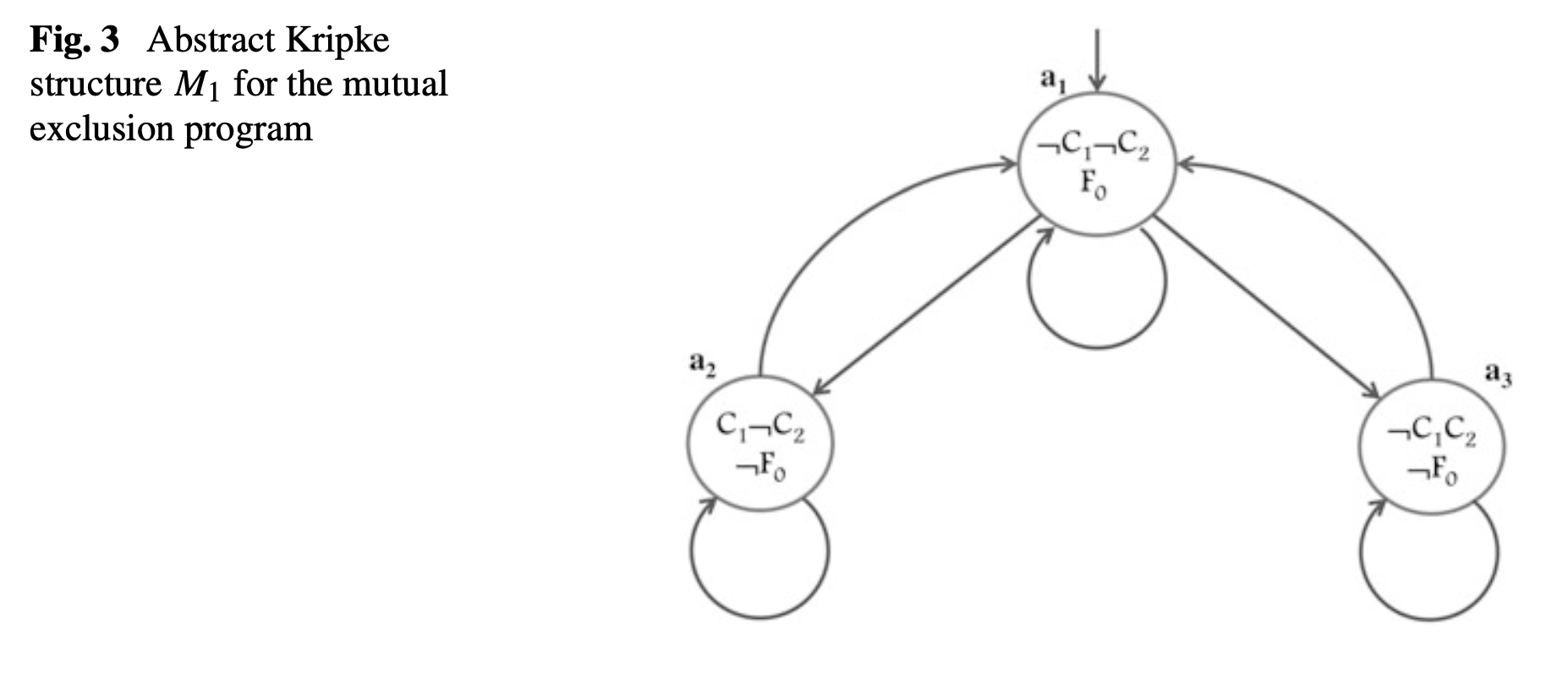

For computation tree logic (CTL), there is a model-checking algorithm whose running time depends linearly on the size of the Kripke structure and on the length of the CTL formula (E. M. Clarke, Emerson, and Sistla 1986).

LTL Model Checking

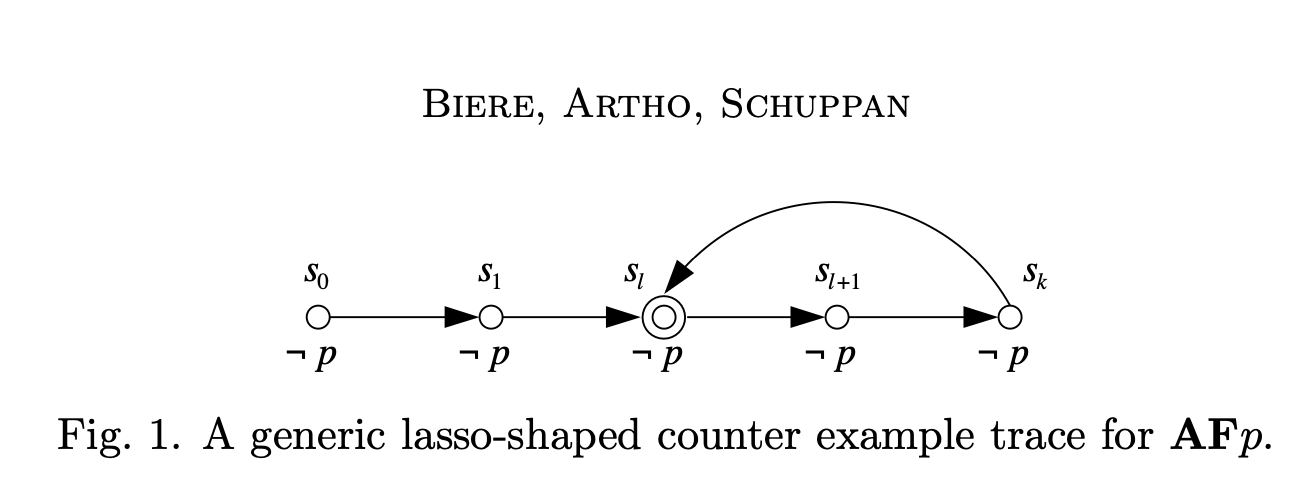

For linear temporal logic (LTL) it is the case that any counterexample to a property \(\psi\) is w.l.o.g. restricted to have a “lasso” shape \(v\cdot w^{\omega}\) i.e., an initial path (prefix) followed by an infinitely repeated finite path (cycle) (Wolper, Vardi, and Sistla 1983). Certain LTL properties have even simpler counterexamples e.g. safety properties always have finite paths as counterexamples. Note that the “lasso”-ness of LTL counterexamples is exploited in certain model checking approaches e.g. some liveness to safety reductions (Biere, Artho, and Schuppan 2002a).

There is an LTL model checking algorithm whose running time depends linearly on the size of the Kripke structure and exponentially on the length of the LTL formula (Lichtenstein and Pnueli 1985). This is done by translating an LTL specification \(\psi\) into a Büchi automata \(B_{\psi}\) over the alphabet \(2^A\) (where \(A\) is the set of atomic propositions) such that for all Kripke structures \(K\) and infinite paths \(\pi\), the infinite word \(L(\pi)\) is accepted by \(B_{\psi}\) iff \(\pi\) is a counterexample of \(\psi\) in \(K\). The size of the automaton \(B_{\psi}\), though, can be exponential in the length of the formula \(\psi\).

More precisely, we translate the negation of our property \(\neg \psi\) into a Buchi automaton, and then consider the product of this automaton with our original system \(K \times B_{\neg \psi}\). The problem then reduces to checking whether there are any accepting runs in \(K \times B_{\neg \psi}\). Recall that an accepting run in a (deterministic) Buchi automaton is any run that visits an accepting state infinitely often. A standard algorithm for checking existence of an accepting run consists of

Consider the automaton as a directed graph and decompose it into its strongly connected components (SCCs).

Run a search to find which SCCs are reachable from the initial state

Check whether there is a non-trivial SCC (i.e. consists of \(\geq 1\) vertex) that is reachable and contains an accepting state.

Technically, the LTL model checking problem is PSPACE-complete (Sistla and Clarke 1985), but it’s worth keeping in mind that in practice the limiting complexity factor is usually the size of a system’s state space, rather than the size of the temporal specification. (TODO: why PSPACE?)

Liveness to Safety Translation

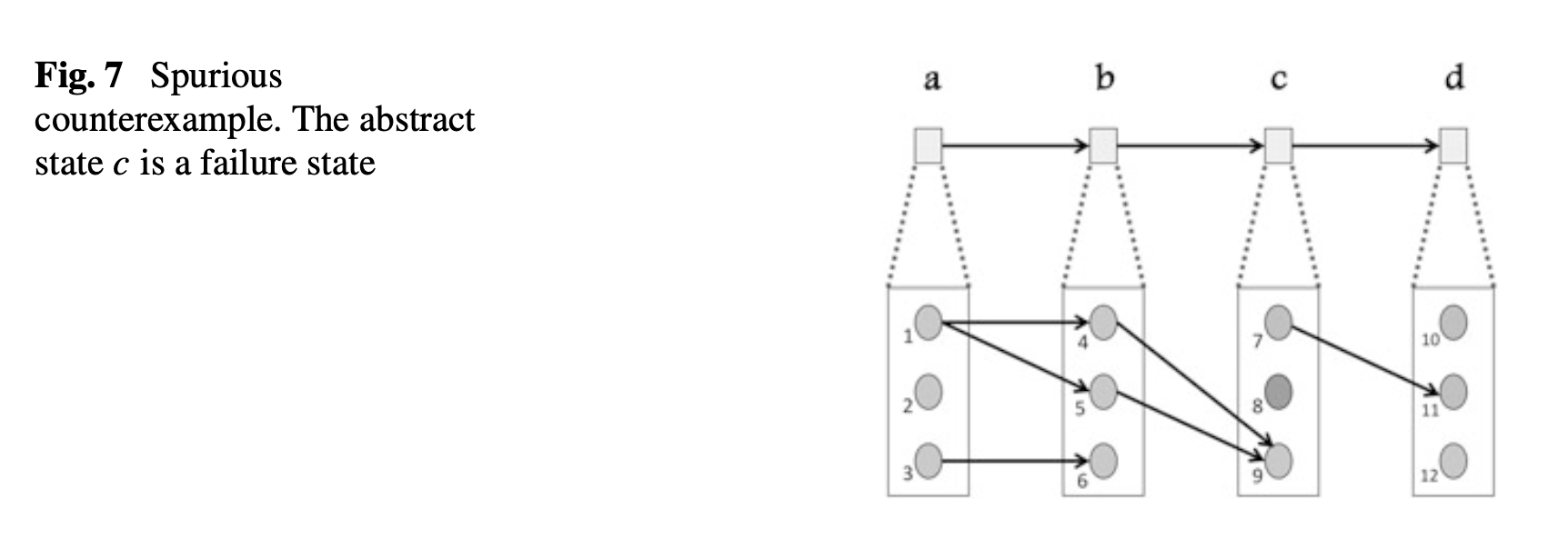

Safety checking (e.g. checking invariants) amounts to reachability analysis on the state graph of a transition system/Kripke structure. It turns out we can apply the same verification approach to liveness properties, motivated by the fact that violations to liveness properties in finite systems are lasso-shaped i.e. they consist of a prefix that leads to a loop. The problem then becomes how to detect such a loop. In the translation given in (Biere, Artho, and Schuppan 2002b), the loop is found by saving a previously visited state and later checking whether the current state already occurred.